It doesn’t take long to grasp the basics of shooting…

The cartridge goes in the chamber, you pull the trigger, the gun goes bang, and (hopefully) you hit the target.

As a concept, it’s pretty straightforward.

But have you ever wondered about the different components that work together to give you that pew pew power?

Consider this an Intro to Firearms Ammunition 101.

This article is for shooters who want a brief but comprehensive run-through of the science that goes into the anatomy of a cartridge.

Today, we’re going to take a look at the four basic components of the modern cartridge so you can become the expert gunner you are meant to be!

Table of Contents

Loading…

Anatomy of a Cartridge

How often has an action star cried, “I need more bullets!” as he faces the world’s greatest cinematic threat?

First things first: A bullet is a solid projectile that is housed inside a cartridge until you make it go boom.

While the word “bullet” is often tossed around as a colloquial stand-in for “cartridge” or “round,” it’s really just one component – the part that shoots out of the gun – of the complete package.

When someone asks for more bullets, they actually mean cartridges.

Terminology is important, so be careful to make this distinction when you go shopping for ammunition or participate in community events, like shooting competitions.

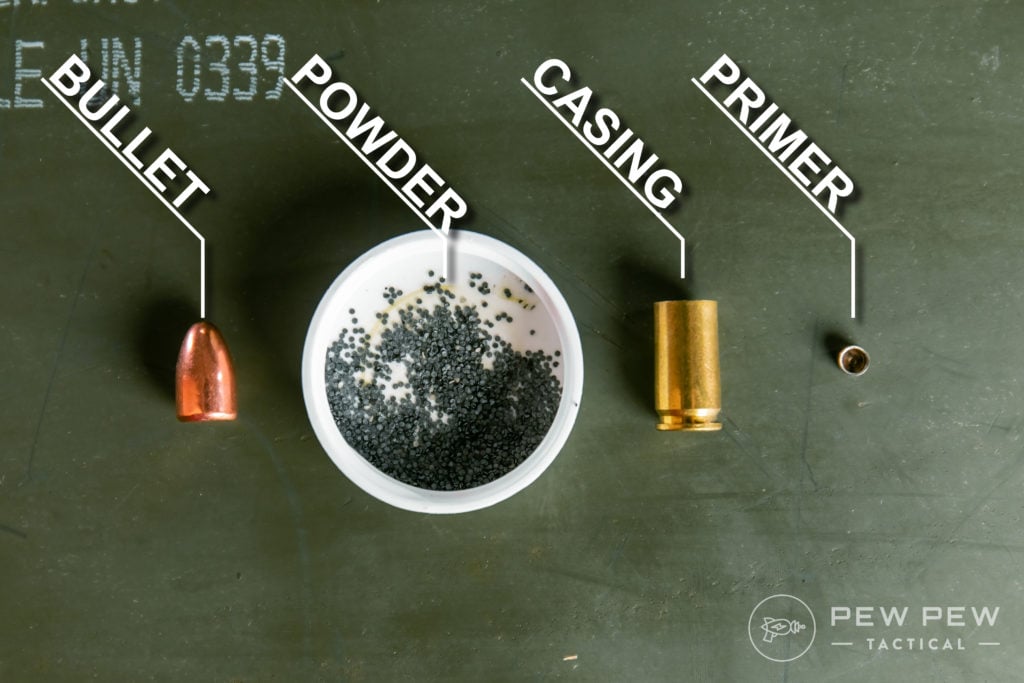

A standard cartridge is comprised of the following components:

- Projectile: This is the actual bullet – or boolit – that leaves the barrel and punches that evil paper.

- Powder: The boom to the stick. Powder is the actual propellant that moves the projectile.

- Case: The shell of the cartridge. It keeps everything together until you’re ready to get busy.

- Primer: Technically, this is the boom to the powder. It’s a percussion charge on a small scale.

Now that you have a basic picture in your head, we can take a closer look at the fundamentals.

1. The Projectile

Due to popular misconceptions, this is the component that tends to be the most confusing to new shooters, and understandably so.

Simply put, a bullet is the projectile that gets sent down the barrel to strike your target.

Composition Of A Bullet

Bullets are usually made out of pure lead or copper-coated lead, but other materials are available, including steel, bismuth, polymer, and rubber.

As an interesting side note, many states have restricted or outright prohibited (California) hunters from using lead projectiles in an effort to protect endangered species.

It’s a long and controversial story, but it has resulted in some unique ammo alternatives; today, many ammunition companies manufacture lead-free compounds that are remarkably effective.

For example, frangible ammunition has gained some popularity in the last few years because it leaves little residue, is comparatively lighter and safer to use, and is completely legal.

Mind you, there are some significant drawbacks to these projectiles since they are lighter and longer than most traditional options.

For those who haven’t read Ken Whitmore’s article on the barrel twist rate, the length of a projectile can influence your accuracy.

Frangible ammunition is customarily polymer-mixed copper or some weird chemistry experiment gone haywire. But it’s still a good training projectile.

To learn more about “frangibles” and their uses, check out Best Frangible Ammo: [Purpose & Calibers].

Our friend Kat plays defense attorney by explaining why this ammo is great for hunting, self-defense, and a fun day of shooting.

Projectiles are often made from pure copper and copper-plated or copper-jacketed lead. These bullets are preferred by many because they have similar weights when assembled.

Of course, as I mentioned earlier, there are times when another material, like polymer, will be added into the mix to get around physics limitations or local laws that have restrictions relating to hollow-point bullets.

By far, my preferred projectile choice is pure cast lead; to be exact, Lyman #2 mixture lead.

Lyman #2 is an alloy mixture of lead, tin, and antimony to achieve a specific hardness.

There are other cast boolit types that are less favored because of weight differences (I’m looking at you, Zinc) but are just as effective.

All cast shots require some type of lubrication to safely and cleanly move down the bore of the gun.

Something unique to lead and zinc projectiles is the addition of a polymer coating. Since most lead projectiles are cast at home, and not purchased, they can be coated with a baked-on polymer.

The cool peeps in the know call this type of bullet a “PC boolit.”

This coating can replace the lubrication essential for cast ammunition and even makes the bullets a bit more durable.

And when I say durable, I mean that they won’t fragment as easily upon impact.

Bullet Shape & Velocity

Projectiles come in several different shapes, or “profiles,” depending on their intended purpose: Boattail, Spitzer Boattail, Hollow Point, Hollow Point Boattail, Flat Nose, Round Nose, Soft Point, Spitzer Point, Semi-Wadcutter, Wadcutter, and a few other variations make up the bulk of all bullet types.

A bullet’s profile can influence its stability, ballistic coefficient, and even how it performs at varying distances.

An ammunition manufacturer or handloader needs to consider a bullet’s intended purpose before picking its shape.

For example, bullets that expand quickly or even completely disintegrate should be used for game animals.

The quick and rapid expansion results in greater damage and a quick kill…even though it means I might have to pick lead out of my venison steak.

Alternatively, you’ll want to use hard and completely jacketed bullet types for target practice.

NOTE: FMJ (full metal jacket) bullets are common target practice rounds and a favorite of the military.

Velocity becomes a major factor when selecting a bullet for a specific application.

High-velocity bullets need to have a strong jacket or risk breaking apart when fired from a gun. Otherwise, it would splatter all over the target like a Jackson Pollock painting.

In summary: Strength is a requirement for fast-moving projectiles. Hunting rounds, however, only need to go slow and expand.

If a target is too far away, the bullet may lose too much velocity and fail to properly expand when striking a target.

There’s a lot to consider!

2. The Powder

If the powerhouse of the cell is the mitochondria, then the powerhouse of ammunition is the powder.

There is a lot of information to cover on the topic of propellant alone – way too much for a simple intro to cartridges guide.

Tl;dr version: You need the powder to fire a bullet more than 20 feet past your barrel muzzle.

Powder choice can be a mystifying topic, especially for newbie shooters and handloaders.

Every type of propellant is designed for a specific range or type of bullet. Pistol powders are for pistol calibers, rifle powders are for rifle calibers, and so on and so forth.

To make it more confusing, people even use pistol powders in rifles – not recommended – for cowboy action loads or super low-velocity loads with GIANT bullets. Slow and steady, baby.

Every powder has a burn rate, and with many different manufacturers giving their products crazy names – I’m looking at you, BlueDot, RX7, Unique, N135, etc. – it’s hard to tell how quickly a powder will burn based purely on its label.

Heck, you can’t even predict burn rate based on grain shape, and powders come in several shapes, including wafer, tubular, spherical, dick, rod, and more.

The variety is endless.

When it comes to powder, grains that have a larger surface area will generally burn faster because, well, more surface means more fuel!

Powder burn rate refers to how fast the powder releases its energy.

Basically, a faster burn rate is for shotguns, pistols, and cowboy rifle calibers, while a slower burn rate is geared toward rifles.

This is a general guideline and by no means a rule, but it helps to understand why powders burn at different rates. Chamber pressures also come into play, but we’ll save that rabbit hole for another day.

A charge refers to the amount of powder inserted into the ammunition.

This is measured in grains and generally has a minimum and maximum recommended powder weight – or charge – depending on the desired velocity.

Compressed charges are pushed and compressed by the base of the bullet. Not all guns can handle this since it raises the amount of pressure exerted in the chamber.

Improperly loaded ammunition that contains a significantly compressed charge can lead to guns blowing up and lost fingers.

3. The Case

The basic measurement of a cartridge case is called the SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute) spec. All new and reloaded cases should be well within these predefined tolerances.

As always, some exceptions exist, but let’s stick to the tried and true SAAMI spec.

A case is more than the outer shell of a cartridge. It contributes to the overall performance and quality of the ammunition.

Most factory-loaded ammunition uses proprietary cases (Winchester, Remington, Lapua, etc.), but some companies exclusively focus on making cases for themselves and other ammunition manufacturers.

Companies like Lapua and Starline produce some of the best — and thickest — cases on the market.

Case wall thickness is important because it affects two critical characteristics of the ammunition: capacity and pressure.

Thicker cases are are reloadable and can handle some pretty significant abuse.

Ammo specifications are generally measured by exterior dimensions to ensure that a cartridge will fit into a gun chamber.

The diameter on the inside of one cartridge may not be as ample as a product from another manufacturer. This can be good or bad, depending on a shooter’s needs.

The Good

A cartridge with a thick casing can be used and reloaded multiple times without splitting or cracking.

In bottleneck cartridges, a thicker case is also better for non-crimped neck tension loaded ammunition. These types of rounds are necessary for high precision and long-range shooting.

Outside of functionality, a smaller interior means that your cartridges consume less gunpowder, which can save you some money.

The Bad

My goodness, it’s expensive! It’s like buying a baby just to use the diapers.

If precision is an absolute must, then these cartridges are great. You absolutely get what you pay for.

But if that’s not your game, then buying new might not be worth the extra cost.

Even though the interior space uses less powder, it can increase the overall pressures of the ammunition — sometimes to hazardous levels.

Lastly, they are a pain in the ass to reload. Resizing them means extra stress on the tools and more case trimming with each reload.

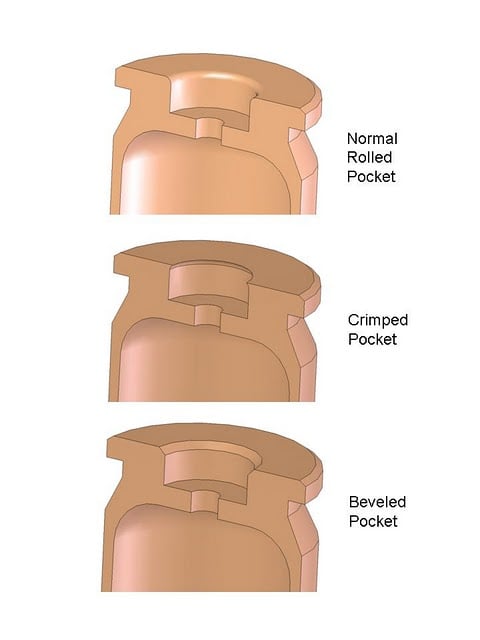

The Primer Pocket

Primer pockets are a necessary component of any proper centerfire cartridge.

This is the part of the case that holds the primer, which is the explosive component that ignites the powder and forces the bullet down the barrel.

As you can probably guess, variations in pocket primer size and depth can adversely affect ignition and reduce your accuracy.

It’s always the little things!

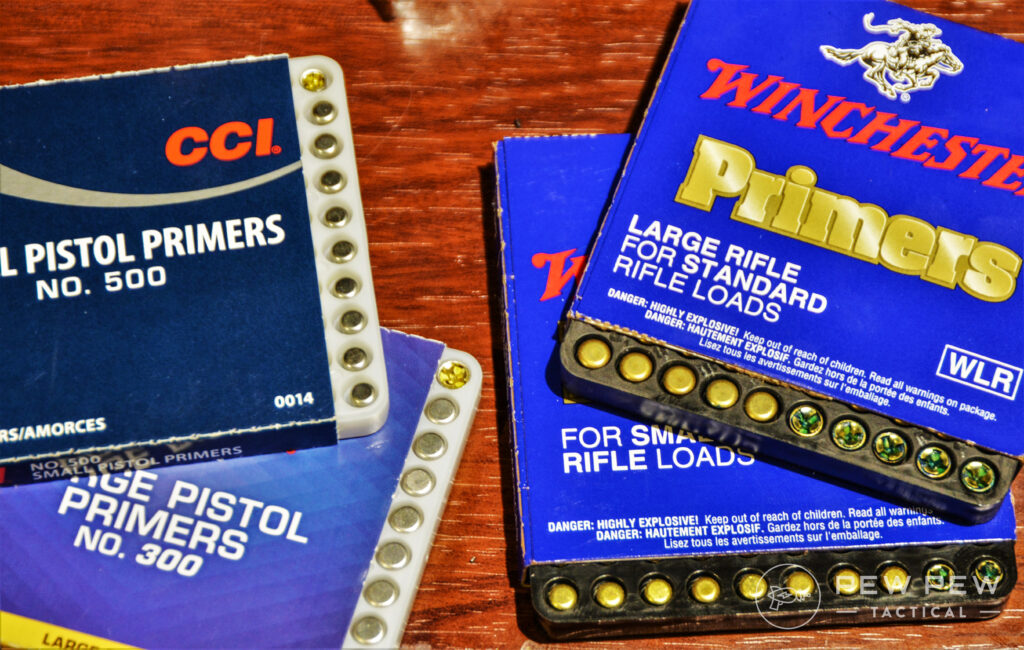

There are small and large primers available for both pistols and rifles, resulting in a combined total of four general pocket types.

But it doesn’t end there!

Magnum cartridges often require a specialized magnum primer, which contains more chemical accelerant than a standard primer of the same diameter.

Likewise, some cases that take small primers might have a sister cartridge in the same caliber that takes a larger primer.

This is usually to offset the use of magnum primers or because case development has changed over time.

On military brass, the primer pockets are crimped.

Since most military rifles have free float firing pins, the primer is crimped and set deeper to prevent it from moving.

This is because military ammo is made quickly and might not be perfectly uniform from batch to batch.

Regardless, crimped primer cases can still be reloaded when swaged.

What Is A Case Made Of?

Cases are usually comprised of brass, aluminum, or steel.

Most steel-cased ammunition that is manufactured in eastern Europe or Russia uses a Berdan primer, which can be a little less friendly to handloaders.

But it all depends on the caliber of choice, as 9mm is almost always Boxer primed.

Steel is usually cheaper than brass, but it’s harder on machines and far more difficult to reload. The same can be said for aluminum cases.

4. The Primer

Alright, we’ve discussed the primer pocket, so it’s only right to move on to the primer itself!

The primer is a small percussion sensitive explosive located at the base of the cartridge. Its sole purpose is to trigger a chain reaction by igniting the gun powder.

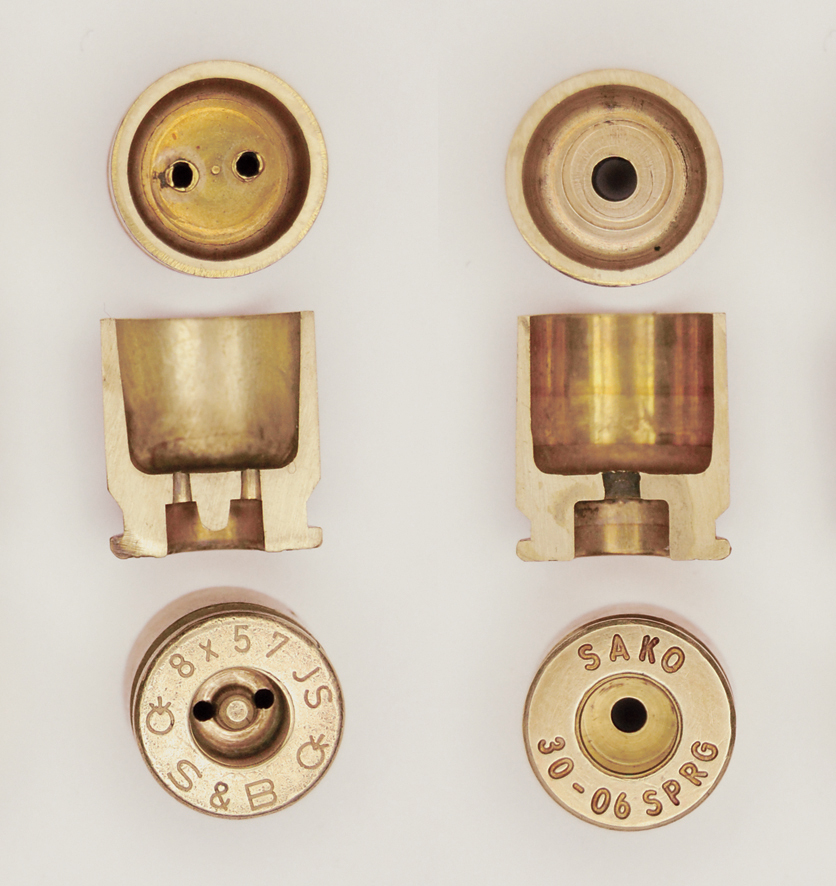

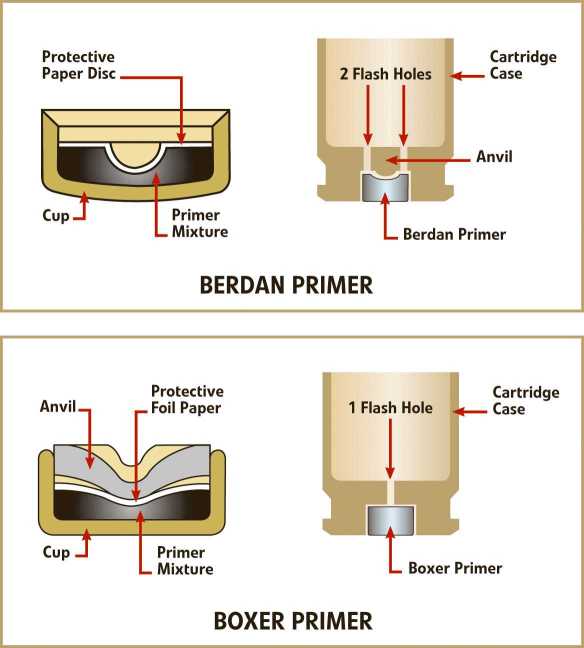

Primers come in two main types, Berdan and Boxer.

Berdan Primers

Berdan is an older style primer that is commonly used in steel cases and com-block ammunition.

It’s horrible. I hate it. Not because it’s bad or unreliable, but because it’s near impossible to reload.

Once the primer is struck by the firing pin, the two small holes above the primer act like mini-volcanos and shoot hot fire into the case.

These two holes make it impossible to easily remove the primer. Historically, these types of primers are also highly corrosive.

Why do Berdan primers still exist if they are such a pain? They are easier to manufacture, reform, and reuse.

It’s basically just a copper or brass cup packed with chemical explosives.

If the end of the world was upon us, and someone needed to manufacture a ton of disposable, non-reloadable ammunition, this is the type of primer they would choose.

Boxer Primers

To the surprise of no one, Boxer primers are more commonly used in modern ammunition manufacturing.

It’s easily the most popular primer style manufactured in the United States.

A Boxer primer contains a small, inverted anvil that sits on top of the chemical explosive in the cup.

Because of this little anvil, the primer can function with less primer mixture. The anvil also creates additional pressure to produce a wider dispersion.

This may be one of the reasons it’s forced through one tiny hole into the case, but I’m no engineer or physicist.

Primers with an anvil are harder to reuse because of the small, fine pieces that need to be disassembled, put into place, and then reassembled.

Fun fact: Rimfire cartridges are an all-in-one case and primer combo.

One of the dangers of using an improperly seated or ill-fitting primer is the risk of gas escaping around the cup.

When a bolt face experiences a gas leakage, it’s like a repeated blowtorch to the face of the bolt.

Safety First: Good Ammo Vs. Bad Ammo

I have one last piece of advice for you before we part ways, and that is to always keep an eye out for risky cartridges.

Cartridges can be easily damaged in a number of ways. Never gamble with your safety by firing an iffy round.

For example, when it comes to old or handloaded rounds, you need to pay attention to any hints of rust or corrosion, particularly around the primer.

And never trust a cartridge if the primer isn’t seated correctly or the bullet is angled strangely.

The same policy applies if the bullet appears to be pushed into the case. This is called “bullet setback,” and it can blow up your gun.

Unfortunately, you also need to be careful with factory rounds. Even major brands have been known to produce ammunition that’s defective in either quality or construction.

Now, don’t get me wrong. Modern ammunition is largely safe and stable…but every so often you’ll come across a round that makes you wonder if a monkey was operating the machines.

And while we’re on the subject, it’s important to remember that many factory machines are automated, so it’s unlikely that a human being performs safety checks to ensure that each round is safe and perfect before it leaves the factory.

Bad ammunition is bound to get through.

Luckily, you can use your peepers to sweep new boxes for bad ammo.

The first and easiest step is to check if the cartridges have been crushed or damaged during shipping or storage.

Next, evaluate the lengths of the individual cartridges. If all of the ammunition is uniform in size and shape, you can logically presume that the machine was set for accurate bullet seating.

Finally, review every round for dents, pits, cracks, bulging, split cases, and improperly crimped case mouths.

Do not use the cartridge if you observe any of these flaws.

Again, accidents caused by poorly made ammunition are few and far between. You probably have a better chance of winning the lottery.

But when it comes to safety, you never want to be the exception, so check your ammo.

If you do find a few bad apples, don’t toss them in the trash.

Your friendly neighborhood sanitation workers won’t appreciate what happens when the compactor sets off your discarded ammo…nor will the people who suffer property damage or physical injuries.

You can get rid of unwanted cartridges by visiting a reputable gun range, contacting your local police department to use their disposal service, or by calling the waste management department to schedule a drop-off or pick-up date.

Parting Shots

And there you have it!

Bullet, powder, case, and primer – the four basic but essential components of the modern cartridge. When you put all of these parts together (correctly), you have a nice round of functional ammunition.

It’s truly amazing how many tiny pieces are needed to make one bullet fire out of a rifle.

Don’t feel bad if you’re still a little iffy on the details. Cartridge construction and reloading are two complicated practices that frustrate many shooters.

Now that you know the lingo, you can go forth into that forum discussion without fear (maybe some fear) or ask questions below. We’re always happy to help.

Have any questions? Or are you a rockstar with some tips and advice for new gun enthusiasts? Either way, feel free to comment below!

Still feeling a little confused? Chin up, friend. We’ve got you covered. Hop on over to the Beginner’s Guide to Reloading Ammo [2020] and our definitive resource on the subject, Ammo & Reloading.

4 Leave a Reply

I'm a rock star but not a rocket man... and not nearly as attractive as the gal in the picture above...

There was a point in time where I considered reloading, but it truly is a hobby. This is a pretty good break down of all the moving parts in the make up of a “bullet”. I don’t know if now is a good time to start reloading or if it makes sense for someone that just goes to the range.

Forget about getting into reloading right now.

You WILL NOT be able to obtain primers unless you plan on reloading .50BMG

Congratulations on getting through an article on ammunition with minimal use of the word 'casing', or (gulp!) the dreaded 'shell casing'. C'mon people, they are cases, no added verbiage is needed. Shells go in shotguns. Those things that litter the ground at crime scenes are not shell casings.