What is a gun guy to do when ammo costs are high, ranges are packed, and I’m bored on a summer day?

Well, I’m not a beach guy, but I am a bushcraft guy…a very amateur bushcraft guy.

After writing an article on bushcraft knives, I fell in love with bushcraft skills. It gave me a renewed vigor to get back outdoors and start exploring, building, and learning.

I’ve been working through a variety of basic skills in the bushcraft community.

And you guys know I love sharing my knowledge with you. So, I’ve taken my five favorite skills and broken them down for you.

I want to walk you through each one so that maybe you’ll pick up a new hobby or learn something. Either way, it should be fun.

So, keep reading if you want to learn essential bushcraft skills.

Essential Bushcraft Skills

1. Feather Stick

Making fire in the wilderness is a skill that’s incredibly valuable, and feather sticks help you do just that.

I’ve been practicing making fire, but my area has been drenched with rain. Absolutely tons of it — that’s expected in Florida’s summers.

That’s where a feather stick comes in handy.

If you search for small debris to create a fire, but everything’s wet, you make a feather stick.

When conditions are dry, but you can’t find the small fuels to start a fire, then you can make a feather stick.

A feather stick allows you to take a big stick and turn it into fine fuels to serve as kindling when starting a fire.

The name comes from the feathers you carve as you drive down into the stick and shave it.

You shave feathers that are thin curls of wood that act as kindling – they should remain a part of the larger stick.

These thin portions of wood ignite quickly, creating a fire.

To make a feather stick, you need to find a good dead stick…not a pulpy, moldy stick. Dead and dry is best.

And we don’t mean a log…you want a reasonably small stick no more than a few inches in diameter.

On the other hand, avoid twigs. These are so thin they absorb moisture all the way through. Best practice is nothing smaller than 1.5-inches in diameter.

You’ll also need a good knife, and my favorite bushcraft knife is the Mora Garberg.

Prices accurate at time of writing

Prices accurate at time of writing

-

25% off all OAKLEY products - OAKLEY25

Copied! Visit Merchant

But if that’s not your style, no worries. We have more options in our Survival Knives article.

If you can’t find something in that magic size range, a larger stick that you can baton into smaller sticks will work.

What is batoning, you ask?

Batoning means turning a knife into an ax and splitting wood.

If the wood is wet, then it’s smart to shave off the wet portion, exposing the dry portion underneath.

Once you have an appropriately sized stick, hold it vertically or close to that with the stick braced against a rock or another piece of wood.

Position your knife along the side of the wood as if you intend to shave it. Use the portion of the blade closest to the handle to do so.

Press the blade into the wood to cut into, and as you press, turn the knife’s edge inwards.

Try and apply even pressure as you push, or the knife might jump and send the feather flying.

That inward motion will create the feather as the knife shaves downwards.

Your first few feathers will likely detach and fall off. That’s to be expected. But they can still be used as tinder.

It will be easier to cut continuous feathers after the stick becomes somewhat smooth from your initial shavings.

Your goal is to keep the feathers attached to the stick as you shave downwards in one continuous motion. Aim to make each feather end at roughly the same point.

Try to maintain even pressure and depth as you press and shave. That’s not easy to do and requires practice.

Make as many feathers as possible. Once the stick becomes somewhat flimsy, you’ve carved enough feathers.

The stick portion will become part of the tinder, and the feathers should ignite the stick itself.

Admittedly, this is not an easy task.

My first few tries were terrible. The best I could do was still pretty bad.

I couldn’t draw a feather to save my life when I began, and while I’m still no expert, my skills got a little better with each try.

2. Figure 4 Deadfall Trap

I was fascinated by the idea of snares as a kid. Not necessarily animals, but like the crazy, bad action movies style.

As you’d imagine, building a snare or trap that big is tricky. But the idea persisted, and I wanted to learn how to build more useful survival traps.

Snares are cool, but the Figure 4 Trap appeals more to me. This trap doesn’t require any fancy snares, rope, or tree. Everything you need to build can be found in nature.

What kind of supplies are needed?

First, you’ll need three sticks roughly 6- to 8-inches long. They should all be close to the same size and made from dead but unrotted wood. Oh, and they should be 1- to 2-inches in diameter.

You’ll need a heavy long, rock or something capable of smashing a small animal. Of course, you’ll need your knife as well.

Building this trap doesn’t take much work, quick and easy to make.

First, you’ll need to know the sticks.

The first is your stake, the second is your cross joint, and the third is the diagonal stick.

They combine to form the shape of the number four — that’s where the name comes from.

Let’s start with the base. It will rest on the ground, preferably against a rock or flatter piece of wood.

You’ll need to carve one end into a point but make it into a flat point (not a spear-type round point).

Next, we’ll carve the diagonal portion of the four.

Designate one side the top and one side the bottom. Starting at the top, move down about an inch. Whittle out a small notch that interacts and fits the flat spearhead of the base.

On the opposite end, carve the bottom into another flat point spearhead.

Finally, we’ll use the cross joint and centerpiece of our four.

This can be a pain because it needs to function with both the base and the diagonal portion of our Figure 4 Deadfall Trap.

Designate a front and rear. Take the rear and carve a notch to accommodate the spear point of the diagonal piece.

Carve the front into a spear point that holds whatever bait you choose.

Finally, in the center, carve a notch to lock into the base of the trap.

You might need to also notch the base to ensure the cross joint locks into the base when pressure is applied.

I had to do that very task to make my setup work.

The notch should be on the same side as the bait tip and hook onto the base.

Set the base into the ground, take the diagonal portion, and hook the top of the base stick into the notch you carved into the diagonal stick.

Use the horizontal portion, and lock the diagonal portion of the trap into a notch you carved in the cross point.

Set the rock against the diagonal portion of the four. Tension holds it together.

When a pesky wabbit stumbles across your bait, triggering the trap, the heavy rock or log will pin and crush the animal.

Obviously, this is a survival trap, not an actual means of hunting. So, do this only in a survival scenario.

Ethical, humane hunting exists, and this trap isn’t it. (After these photos were taken, my trap was taken down and discarded.)

3. Ferro Rod Fire

I approached Ferro Rods with the idea that “Oh, this will be easy!”

It turns out I was quite wrong.

Maybe it’s a life of adventure movies that convinced me I could be a master of fire! But it turns out, using a Ferro Rod takes practice, patience, and technique.

Ferro Rods are made from ferrocerium – it’s 70 percent cerium and 30 percent iron.

When struck, they spark and burn at over 5,000 degrees. Though they look incredibly small, they pack a lot of fire into a small rod design.

Again, I grabbed my Mora Garberg and its square spine for this task. You don’t strike the rod with the blade but with the spine. A square spine makes an awesome striker.

Prices accurate at time of writing

Prices accurate at time of writing

-

25% off all OAKLEY products - OAKLEY25

Copied! Visit Merchant

You’ll need ultra-thin and small materials to act as tinder. Old bird nests, dead grass, small dead plants, or a feather stick will work.

Note: You need dry tinder because we shoot sparks into dry tinder.

First things first, carve off the black finish. This rust protectant gets in the way of your work. Learn from my mistakes.

First, gather your tinder with other tinder within arm’s reach to keep the flame going.

Second, work in a place where you can get a fire started beyond your tinder pile.

Third, don’t strike the Ferro Rod hard and fast – go slow, start from the top, and move slowly.

When I say move, don’t move the knife. In fact, I hold my knife, or striker still, as I run the Ferro Rod from rear to front across the spine slowly.

Going slow creates sparks, casting a controlled amount into your tinder.

I hit my tinder several times when striking the rod with the knife instead of vice versa.

Also, I learned that if you can grind off some Ferro shavings (not ignited) into your tinder and then hit it with sparks, you can spring a fire up quite quickly.

In the beginning, it can feel quite frustrating. What seems simple becomes difficult quickly.

Practice, practice, practice. First time you make fire, you’ll feel like Tom Hanks in Castaway.

And if you’re looking to buy a Ferro Rod, make sure you head over to our roundup of the Best Fire Starters!

4. Build a Solar Still

A solar still is an easy way to get water in the great outdoors. However, it does require something more than a knife and nature.

You’ll need a knife, hefty rocks or logs, something to dig with, a tarp/trash bag/plastic-like material, and finally, a container that can hold water.

First, dig a hole in a sunny area. Depth and size will be determined by the size of your plastic material and the size of your container.

Half a water bottle will require a smaller hole than a 5-gallon bucket.

Once your hole is dug, place your container in the middle.

Go forth into the wild and cut down some thin, fresh, green vegetation and pile in the hole around the container.

Now cover that container with your plastic material.

Lock the plastic material down with your heavy rocks and logs.

Completely cover the plastic and pin it to the ground. Prevent it from flapping in the wind.

In the center, over the top of your container, set a rock/log. This forces the bag to slump downward.

The way this works is that the sun heats the material and draws moisture out of it.

As the water dissolves into the heat, it gets captured by the plastic and forms into water drops.

These drops race to the center and drip into the container.

It’s a slow process, but it works quite well for drawing water out of the materials around you.

5. Leaf Hut

Dying from exposure is a very real possibility, and as such, you should be prepared to protect yourself by building a shelter.

A simple leaf and debris shelter isn’t fancy, but it can help you survive and keep the world away from you.

You’ll need to find an area where you can lie down safely. The size of your shelter will be your height plus 6-inches or so.

Sorry tall kings, but we have work to do.

You’ll need to gather a large limb, at least your height plus 6-inches. This will be your beam and should be thick but not big enough to hurt you if it collapses.

Next, you’ll need two large sticks to hold the beam up, with one side resting on the ground. Preferably it should be braced against a tree to prevent it from slipping rearward.

The rule of thumb is that the highest point of your beam shouldn’t be above your knees. The shelter needs to be tight to insulate and contain your body heat.

With one portion of the beam elevated and the other braced into the ground, we start adding the ribs.

By ribs, I mean sticks that rest from the beam to the ground. More is better, and the ribs shouldn’t be much taller than the base. You want as little room between them as possible.

The tighter the ribs are, the more efficient your leaf hut will be at utilizing small leaves.

Once your ribs are in place, it’s time to find your leaves.

Pile the leaves starting at the base, working your way upwards. You want the entire shelter covered in leaves, palmettos, or whatever you can find.

Form a nice thick layer that’s at least 18-inches thick. If you can go thicker, do so. The thicker the leaf layer, the better protection you’ll have from wind and rain.

You should feel a little tight inside the shelter, but this ensures you stay nice and warm.

Final Thoughts

I’m a bushcraft amateur for sure, but I’m learning more daily.

Picking through the books of old bushcrafters, haunting Reddit forums, and of course, playing in the woods, I’ve gathered a few skills.

Hopefully, now you have to.

As an amateur, I have to ask our more experienced bushcrafters what their favorite skills are. What did I miss? Let me know below! Also, if you want to learn from some professionals, check out our list of the Best Wilderness Survival Courses in the U.S.

11 Leave a Reply

Also, I have a photo of a cool little bird trap but don't see a way to attach it.

Leaf hut: I am an architect and I know that all building waterproofing is designed to shed water. If the ribs and the leaves in your leaf hut pointed downward they would shed water better. What say you to this idea? Also, I love fish weirs. So easy and useful.

I just discovered this website via googling how to pee in the woods. I plan to use the strategies in squat toilets in Egypt as well as in the woods.

If near the ocean or lake building a fish weir could provide some food.

When I go backpacking I take a small medicine container filled with cotton balls soaked in vaseline. I forget where I first learned this, but obviously the vaseline repels water and gives the cotton something to wick making it burn slowly and consistently to start a fire even when starting with damp tinder.

Travis, if you'd been raised where I was, you'd have learned about a Solar Still as a young un. Everyone hears Colorado, and thinks mountains. With mountains, you think rivers and streams, and we do have a number of them. Some streams though are seasonal, and for most of the year, .

they're dry as a bone. So learning how to construct a Solar Still here, is essential for survival. You can walk for miles in the Sangre de Cristo and San Juan Ranges and never see water. So you have to find it.

I've not spent any time in Florida, but I have kin in NW Georgia, up in the hills.

Just about every region of the US has unique resources, so it behooves us to study everything about our AO, so we can exploit those resources.

As for fire starting, I always keep at least 3 in my daily kit. A lighter, a ferro rod, and waterproof matches.

As they say, "Keep On Preppin'"

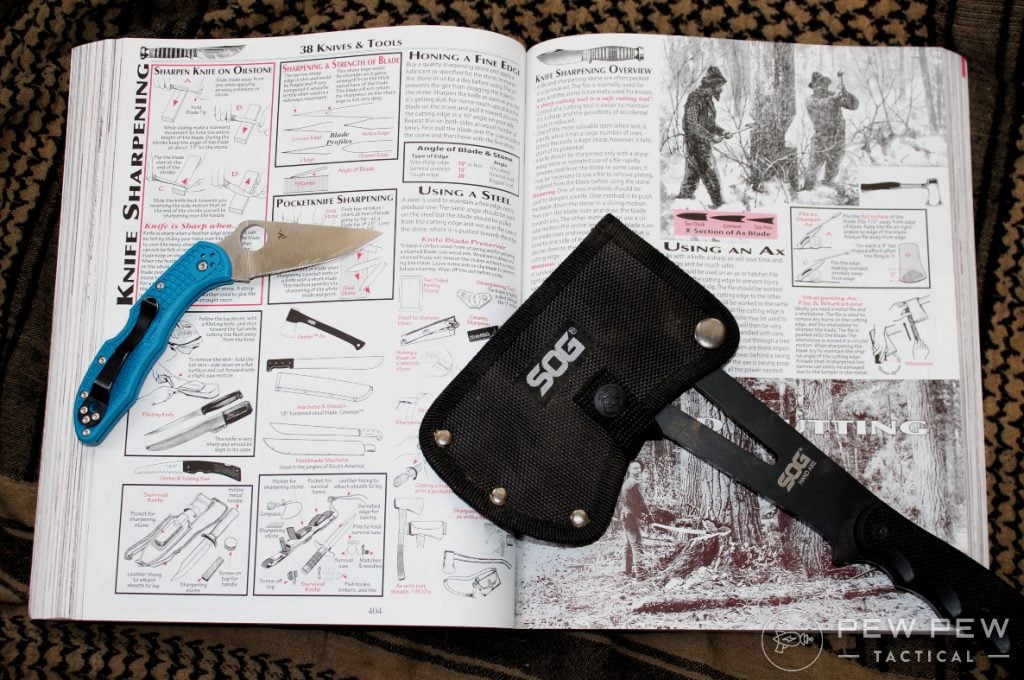

What is that book title with the Spyderco and SOG lying on it? I like that format.

I may be wrong, but I think it is Camping & Wilderness Survival, 2nd: The Ultimate Outdoors Book, Paul Tawrell.

Indeed, found it by tracing back the picture link. ;-) Seems there are two editions, have a used one coming from Amazon. No electronic forms of it are available for anyone interested, only hard copies. Thank You!

My wife's idea of 5 Essential Bushcraft Skills are all called 'room service'

My Dad was in the Vietnam bush for a couple of tours. After that, he used to say, "My idea of roughing it, is a Holiday Inn without room service."

Haha! She and I are on the same page!