While I love all firearms, what really drives my interest are the ones that were almost famous. The ones that might have fallen a bit short and were just shy of greatness.

Some of the best examples of that come from odd-ball places that you might not expect to see, such as Egypt.

Historically, Egypt was never considered a major firearms mecca. However, a time existed in the mid-20th century that found Egypt at the forefront of firearm adoption while at the same time woefully behind the curve.

Much of this dichotomy can be summed up with the adoption and production of the Hakim rifle and Rasheed carbine.

If you want all of this awesome story, make sure to take a look at our video below on these weird rifles.

Also, if you loved this video — subscribe to the Pew Pew Tactical YouTube channel!

Table of Contents

Loading…

Short and Sweet

Let’s start off with what the Hakim and Rasheed are.

The Hakim is largely based on and is in fact almost a copy of the Swedish Automatgevär m/42 (Ag m/42).

Though with a few modifications and chambered in 8mm Mauser instead of 6.5x55mm.

The Rasheed is more or less a copy of the Hakim but downsized and chambered in 7.62x39mm.

Employing a true direct impingement gas system, a tilting bolt design, and semi-auto rate of fire, the Hakim and Rasheed can feel very modern in operation.

But covered with wood furniture, small-ish iron sights, and a detachable box magazine designed for stripper clip reloads, both guns retain an old-world feel to them.

Firearms of the 1950s

To really understand the Hakim and Rasheed, you first should know a little about other firearms of the early 1950s.

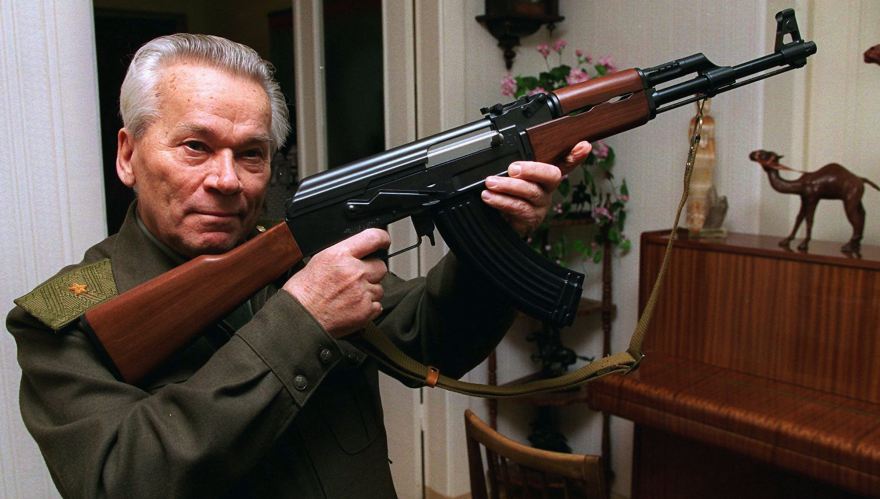

The three major military powers of the early ‘50s were the USA, the UK, and the USSR. Of the three, only the Soviets really had a truly modern rifle in the AK-47.

In the United Kingdom, they were still using the Lee-Enfield No. 4 and No. 5 Mk I in .303 British.

While technically adopted in 1951, the EM-2 bullpup lasted for all of about 10 minutes with less than 60 ever made.

The truly modern L1A1 SLR (FAL clone) in 7.62 NATO wouldn’t come into British service until 1956.

We in America were using mostly the M1 Garand in .30-06 in front line service with the M1 and M2 Carbine in .30 Carbine for rear line troops.

The M14 in 7.62 NATO wasn’t accepted for service until 1959. The M16 in .223 Remington, and later 5.56 NATO, wouldn’t come until the mid-1960s.

Over in the USSR, the AK-47 in 7.62x39mm was adopted in 1947 with the AKM arriving in 1959.

This held a significant advantage over rifles in western service and marked the beginning of the modern age in small-caliber select-fire weapons.

And then we look at Egypt and its…interesting firearm selection.

History of the Hakim and Rasheed

I promise we’ll start talking about the Hakim and Rasheed in a moment, but first comes the FN-49.

Before World War II, Egypt and the British Empire were close. In fact, it was a British Protectorate.

During that time the British supplied the Egyptians with .303 Martini-Enfields.

After World War II, Egypt found itself with a massive surplus of 8mm Mauser ammo and some 8mm bolt-action Mausers, mostly due to the German occupation.

Ammo came from a huge range of manufactures and of different quality. The rifles were mostly on the lower end of the quality spectrum, but still very serviceable.

In 1951, King Farouk broke from British influence and wanting to modernize the army’s rifles, ordered nearly 40,000 FN-49s from Belgium.

These chambered in 8mm Mauser were outstanding rifles for their time.

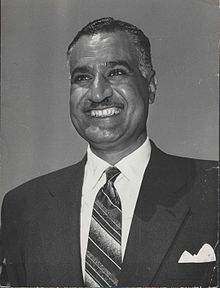

A year later in 1952, Col. Gamal Abdel Nasser staged a coup and King Farouk fled Egypt for Italy where he lived in exile.

Nasser looking to modernize the Egyptian army…again, decided they needed a new rifle.

This time, instead of merely buying a boatload of rifles from a European nation, Nasser wanted Egypt to produce domestic Egyptian small-arms with tooling, technical equipment, and advisers from a European nation.

But the rifle would be based on a European design.

All of this in an attempt to make Egypt more self-reliant and to break away from the heavy western influence that Farouk was hated for.

So you know…normal dictator things.

The rifle chosen to base the Hakim on would be the Swedish Ag m/42.

In case you’re confused: Yes, they decided to replace one rifle with another that was…basically the same thing.

The FN-49 is a semi-automatic, short-stroke piston, fixed magazine, 8mm Mauser, stripper clip fed, rifle.

The Hakim is a semi-automatic, direct impingement, detachable magazine, 8mm Mauser, stripper clip-fed rifle. But note, the detachable magazine was used like a fixed magazine.

However, the Hakim would be produced in Egypt!

…Using a design modified by Swedish engineers and on tooling sold to Egypt that once built the Ag m/42 that the Hakim was based on.

Oh well, close enough.

Hakim Modifications

While the Ag m/42 was the base rifle, there were some changes that needed to be made.

First, a redesign for 8mm Mauser. This wasn’t much of a challenge, but it did substantially increase recoil.

To combat this, they designed a new muzzle brake that was shockingly effective.

The recoil of an Hakim compared to something like a German K98k is stunningly less.

The Hakim design also opts for an adjustable gas block for several reasons. First, Egypt had a huge surplus of 8mm Mauser ammo — but it ranged wildly in quality.

Partly due to being manufactured all over the world and partly due to how the quality of axis ammo, in general, declined as WWII progressed, the supply Egypt was left with was not consistent enough by most standards for a semi-automatic rifle with only one gas setting.

On top of that, as armies around the world discovered and rediscovered for the past 100 years, the sand and dust of the desert wreaks havoc with the gas settings of small arms.

The adjustable gas block uses a small wrench supplied with the rifle to troops. I’ve never seen an original wrench, but reproductions are easy to find.

I pity the poor men that had to carry and drill with the Hakim in the Egyptian desert because this is a thicc rifle.

47-inches overall with a 25-inch barrel and 11-pounds unloaded, the Hakim was an interesting choice to arm the relatively slight of stature Egyptian army of the 1950s.

Roughly 70,000 Hakims were produced in the 1950s, and I’ve read reports ranging from 7,000 to 15,000 of those were imported into the USA. Personally, I would suspect that the lower end of that range is more accurate.

While the Hakim isn’t the rarest historical rifle to be found in the States, it’s definitely not common.

Enter The Rasheed

Sadly, I really don’t have much information about this awesome little carbine.

Even in well-written reference books, there isn’t much more information on the Rasheed than what is found on Wikipedia.

Adopted in 1960, weighing in at 9-pounds, 40-inches overall with a 20.5-inch barrel, the Rasheed is much handier.

Basically, the Rasheed is a scaled-down version of the Hakim with a couple of minor tweaks. The charging system offers a more thumb-friendly design and a folding blade bayonet patterned after the SKS was added.

Chambered in 7.62x39mm, it’s much more suited for infantry use. But…still uses stripper clips. The stripper clips themselves are a proprietary Egyptian design that is slightly more narrow than the SKS standard.

And once more, I’ve never seen or even heard of someone seeing a real Rasheed stripper clip in the USA.

So, we’re stuck with loading our magazines one round at a time.

Other than that, it’s mostly the same rifle as the Hakim.

While I’ve looked high and low, I can’t find a firm source on whether or not the Rasheed was designed domestically by the Egyptians or if it was designed with help from the Swedish advisers that assisted Hakim production.

Or possibly, and I have absolutely no sources to suggest let alone confirm this other than some logic and guessing, Soviet technicians lent a hand with Rasheed production.

The caliber choice, the adoption of the AK from the Soviets just a few years later, and the very obvious SKS influence on the Rasheed…

Of course, Egyptian arms technicians could simply know of and like the SKS, using it as an influence for the Rasheed.

The truth? I don’t know. But if you do and have a source for me to read, please drop it in the comments!!

What I do know — less than 8,000 Rasheed carbines were produced and something like 200 to 500 came into the USA. This makes them a fairly rare carbine to find and much more rare than the Hakim.

Range Report: Hakim

I found my Hakim about a year before I was able to get my hands on the Rasheed, so I have a bit more time shooting it. As a collector’s rifle, it’s freaking awesome.

As a rifle issued to someone who carried it in the desert…mad respect.

The Hakim is heavy and the manual of arms is weird by every standard. While the magazine is detachable, it was never intended for mag reloads.

Instead, the Hakim and the Rasheed reload via a stripper clip. And only one magazine per rifle was issued. My magazine is sadly a modern reproduction but is accurate in every way.

Between the weight of the rifle and the very effective muzzle brake, the recoil feels surprisingly light. It’s still a full-power rifle cartridge, but compared to other 8mm Mauser rifles it’s a lot easier on the shooter.

I would compare it to a strong .308 or maybe a tamed down .270 Win.

The open iron sights aren’t amazing, but they are at least reasonably useful and surprisingly accurate. 200- to 300-yard shots on steel were fairly easy.

On paper at 100-yards, I can get about 3 MOA using match grade PPU 8mm Mauser.

That ain’t bad at all considering the age of the rifle. Not to mention, I suck at iron sight shooting, and match-grade PPU isn’t amazing.

Quirks

Got your thumb bit by an M1? You ain’t seen nothing yet.

The Hakim features a dust cover that pulls triple duty as the dust cover, charging handle, and brass deflector.

Charging the bolt means pushing the dust cover/charging shroud forward and then pulling back. Load up via stripper clips, and give the dust cover/charging shroud a light pull back to release the bolt.

Just be careful not to drop the rifle or give it a good wack while the bolt is back because that can absolutely release the bolt and send it slamming forward.

Want to drop the bolt without loading the rifle?

First, set the lever safety on the rear of the charging shroud to the right for safe. Hold the charging shroud back, depress the magazine follower, and gently lower the bolt.

The Hakim also brings some of the strongest brass ejection of any rifle I’ve ever seen. On the “standard” gas setting this sends brass out with enough force to dent the brass when it strikes the brass deflector.

Since the Hakim was issued with one magazine per rifle, spare original magazines are very hard to find.

Reproductions are fairly easy to track down, but they might require some fitting. Mine needed a decent amount of filing on the catch before it fit.

Range Report: Rasheed

Ever shot an SKS? The Rasheed is basically the same. Except cooler.

Really though, the shooting experience is on par with an SKS.

Personally, I enjoy it. It’s fairly soft shooting, accurate, and feels great in your hand. Slapping steel at 200-yards was simple once we figured out my Rasheed’s hold-offs.

My irons are very badly out of zero and I haven’t taken the time and effort to fix that since I’d rather not risk breaking anything on a rifle that is honestly 95% a safe queen to me.

In every respect, the Rasheed is a more warfighter-friendly weapon than the Hakim is.

While only a fraction of the number was made, I suspect that once the Egyptian army saw how much better the Rasheed was to the Hakim, they quickly decided to pursue a proper modern rifle.

Thus, the adoption of the AK-47 only a couple of years later.

Quirks

Thankfully, the weird charging shroud design of the Hakim is gone. Instead, we have a proper charging handle that is independent of the bolt and non-reciprocating. This also keeps everything inside a bit cleaner.

This is absolutely a design improvement but doesn’t help make the manual of arms between the two simple.

The major quirk of the Rasheed comes in the form of the stripper clips.

As I mentioned before, for reasons that I cannot possibly understand, the Egyptians designed a proprietary stripper clip more narrow than a standard SKS clip. Thus, SKS clips don’t fit.

Personally, I’ve tested three brands of clips.

On forums, I’ve read of people trying basically every clip on the market and so far no current production or surplus clip will fit the Rasheed.

Sadly, I’ve never seen or heard of anyone actually finding real original Egyptian stripper clips.

Unless something changes, it looks like we’re stuck dropping the mag and loading it up with thumbs.

Value of a Hakim or Rasheed

While I would never pretend that I’m an expert in this area, I can at least give you some ideas for what to look for when buying an Hakim or Rasheed.

First of all, don’t be cheap. Every now and then I see one of these rifles sell for half or less of their value because the seller doesn’t know what they have.

It’s not unheard of for a Rasheed to literally sell as an “Egyptian SKS” for under half its real value.

I didn’t win the bid, but I’ve even seen them sold on Gunbroker as “Saudi Arabia SKS.” That’s wrong on like three different levels.

For an Hakim, you’re looking at about $850+ right now with an original magazine.

Note that the Hakim ONLY came with 10-round magazines. If you get one with a 25-round magazine, it’s not a real Hakim magazine.

It’s actually an MG-13 magazine that has been modified slightly to fit an Hakim. Ya…that’s a real thing.

If you can find an original bayonet, those will add about $100 to the price. I highly recommend it, because they are pretty cool.

Compared to the Rasheed, the Hakim is fairly cheap. But feeding it is a lot more expensive. Personally, I would never feed mine anything other than PPU FMJ 8mm Mauser and that’s like 65 cents a round minimum.

The Rasheed, in my opinion, is massively undervalued right now. Current prices are kicking around the $1,100 to $1,300 mark. Seeing as how incredibly few of these are actually in the country, I’m shocked at their price.

Value of historical rifles is more closely linked to their stories than their rarity, but I really think the Rasheed is crazy cheap.

Conclusion

While they aren’t the rarest or the most expensive rifles in my safe, the Hakim and Rasheed are two of the ones I’m most proud to have.

They are, to me, two perfect examples of my “just shy of greatness” test for a firearm.

When each was adopted by Egypt, it was cutting edge and outdated at the same time. Semi-automatic, detachable box magazines, but not designed to reload by changing the magazine, and the Hakim using a full-power rifle cartridge still.

The Rasheed, effectively an SKS with a different action, was what the Hakim should have been from the start — but would be quickly replaced with the AK-47.

They are beautifully made and prime examples of Swedish design, even if they were actually made by Egyptian hands and in Egyptian deserts.

Make sure to see the Hakim and Rasheed in action in our full video review below.

What do you look for in a firearm collection? How do you like these old-rifle reviews? Let us know in the comments! Check out more cool vintage rifles in The Coolest Guns from WWII.

Leave a Reply