So, you want to learn a little more about those nifty “ham radios” you’ve heard about, right?

After all, who wouldn’t want a way to tap into emergency communications?

Oh and one that can be battery-powered, mobile, non-reliant on common infrastructure, and even used to talk to the ISS or bounce a signal around the globe?

I know, I know — it’s super cool! And the best part?

It’s really easy to start.

I would know! I tested for and earned my technician license when I was 11. And, spoiler alert, I’m no electrical engineering whiz kid.

So, if you’re interested in getting your feet wet in the wonderful world of amateur radio…you’re in the right place!

We’re going to walk you through all the basics of becoming a Ham operator, including licensing and regulation, how amateur radio works, and how you can use a ham radio (including in emergencies). Finally, I’ll make a few suggestions for your first rig.

Sound good? Sweet!

Let’s get it!

Table of Contents

Loading…

What is Ham Radio…Exactly?

So, you might have surmised that Ham radio doesn’t actually involve lunchmeat, nor does it involve animals of the porcine persuasion. (…Or you didn’t, and that’s okay. We’re all learning today!)

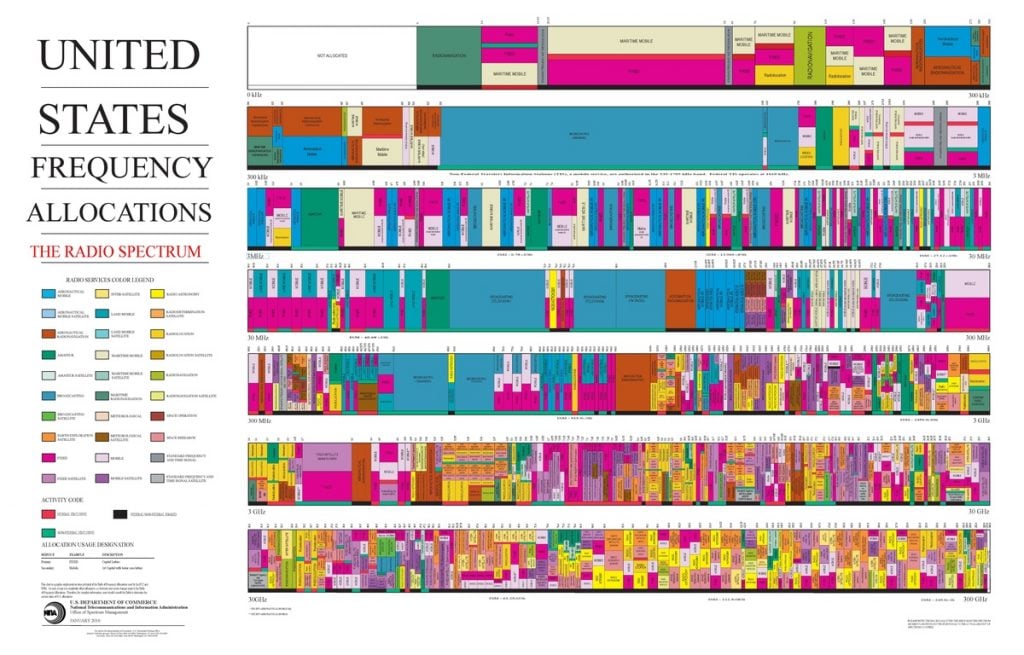

Also called “amateur radio,” ham radio uses a class of radio bands set aside specifically for the purpose of allowing license operators to transmit and receive.

If that sounds weird, let’s look at some other radio bands set aside for specific use: FM radio, AM radio, CB radio, aeronautical and marine communications, radar, radio-control toys and models, police and fire radio…your garage clicker.

All of the above use some portion of the radio spectrum, but the whole spectrum is divided into “bands” dictating who can use which frequencies.

Can you imagine the havoc that would happen if your microwave operated on the same frequency as your local law enforcement?

Or if your garage clicker created interference for jumbo jets trying to land?

Fun fact: a long time ago, in the early days of radio, all frequencies could be used by everyone. This meant amateur operators could disrupt an entire area’s communications by using a frequency that was in use for other things, like communicating with ships.

Professional radio operators started calling amateurs “hams” as a not-so-nice nickname…and the amateurs took it and ran with it!

So, knowing that…these days, amateur radio is the practice of using a specific set of frequencies to communicate. And you must be licensed by the FCC to use those frequencies.

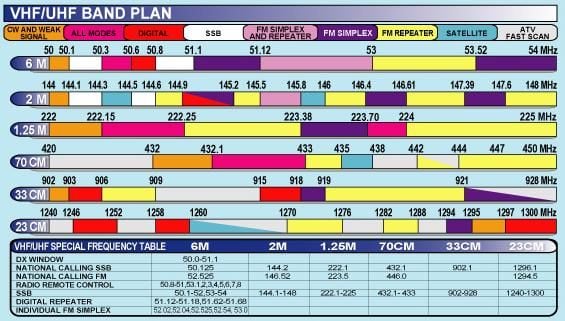

Let’s take a look at which bands you’re entitled to use as a licensed Ham radio operator.

Ham Bands

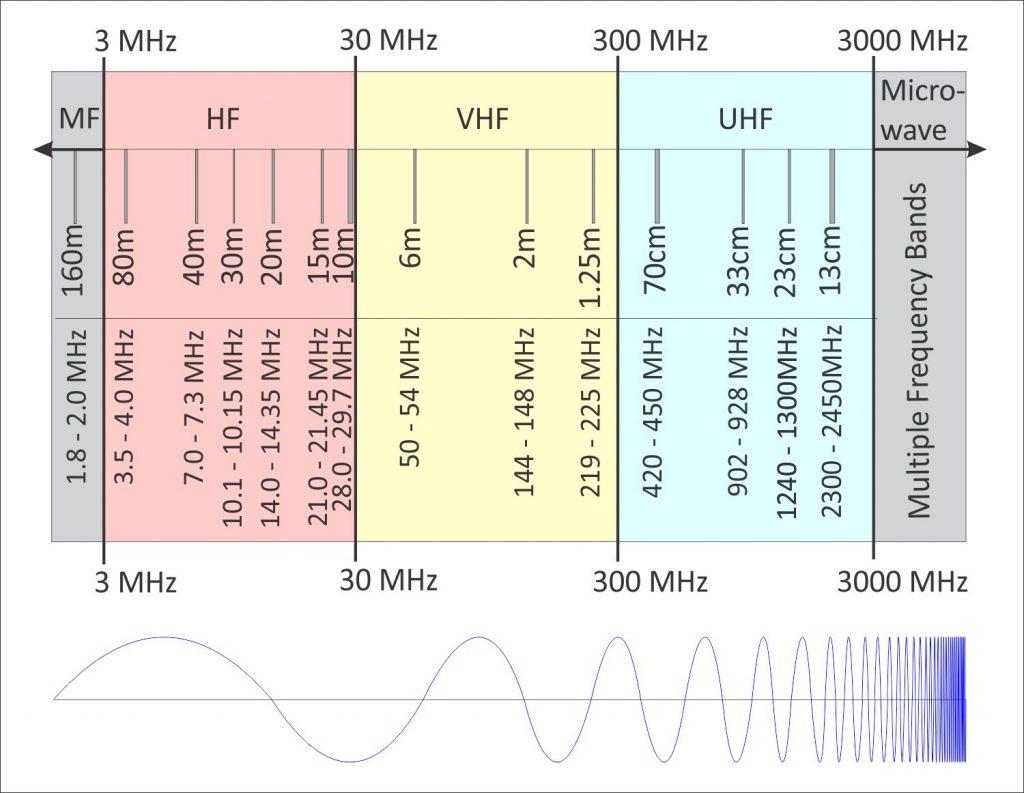

The specifics of Ham frequencies vary between countries (and sometimes even locales), but they do tend to stick to the High Frequency (HF), Very-High Frequency (VHF), or Ultra-High Frequency (UHF) areas of the band.

Don’t worry if you don’t know what that means.

For practical purposes, you’re going to operate on a very limited amount of frequencies as a beginner. I pretty much only operate on the 2-meter band, which means you’ll find me exclusively between 144.1-148.0 MHz, which is VHF.

You might start exploring different frequencies and methods of transmission a little later as you figure out what you like to do with Ham radio, but I don’t want to bog you down with a bunch of “if x, then y” just yet.

Interested in learning more about Ham radio frequencies? The Amateur Radio Relay League, or ARRL, is a great resource.

This is the site of the National Association of Amateur Radio Operators in the U.S.

Actually, if you’re going to get licensed, go ahead and also join the ARRL.

The FCC

I’ve mentioned licensing and frequency restrictions a bit, and you might be wondering…who on earth is responsible for all of this?

Well, that would be the Federal Communications Commission — better known as the FCC.

The FCC handles a lot, including commercial broadcasting, the internet, and pretty much everything radio. So, it shouldn’t surprise you that they also have a finger in the amateur radio pie.

Really, you’ll only ever need to interact with the FCC to get licensed and apply for any special permissions you might want to request. Other than that…they don’t pay too-too much attention to we lowly Hams.

That is unless you get reported for doing one of the no-nos of Ham that I’ll detail in a little bit.

There aren’t too many rules when it comes to Ham radio, but there are a few you need to be mindful of because they can carry some hefty fines, and some even come with criminal charges.

Don’t let that scare you, though. It is pretty dang hard to mess up bad enough that you’ll be reported to the FCC for investigation.

Most amateur operators will give you a warning if you make a mistake.

How Does Ham Radio Work?

Without giving you an entire degree in electrical engineering here, let’s talk in broad terms about how Ham radios work.

You’ll learn all this in much more detail if you choose to get your license so I won’t belabor it too much here.

Like any other radio, Ham radios use radio frequencies to transmit information.

What makes Ham different from something like, say, FM radio, is that pretty much everyone using it has both the power to transmit and receive.

The radio in your car, for instance, is only a receiver. It cannot send a signal — that’s what the radio station does.

Ham is, essentially, a much more powerful walkie-talkie. If you’re using a handheld radio or a car-mounted one, the device is capable of transmitting and receiving, all in one.

If you’re setting up a “ham shack” or a space that you operate from at your home, in an RV, or other non-mobile location…you might use a transmitter and a receiver separately, depending on your setup.

The important part is — you can send messages and receive them.

Ham radio can be used for local communication, but it also can be used to get far. Like, really far.

My personal best is that my dad, brother, and I have DX’d (that’s “identified a signal very far in origin” to you non-Hams) other operators in Russia from my home in California.

The International Space Station often has at least one Ham operator on board, and you can hit them when the conditions are right.

Talk about out of this world!

How you go about doing those things will depend a lot on the amount of power you’re transmitting with (which is regulated by the FCC), what the atmospheric conditions look like, what solar flares are doing, your local topography, using repeaters, and other factors.

You can dig into that more if you’re interested.

Dual-Band and Tri-Band

You might also hear the term “dual-band” or “tri-band” come up when you’re learning about amateur radios. It’s actually a really neat part of how ham radios operate!

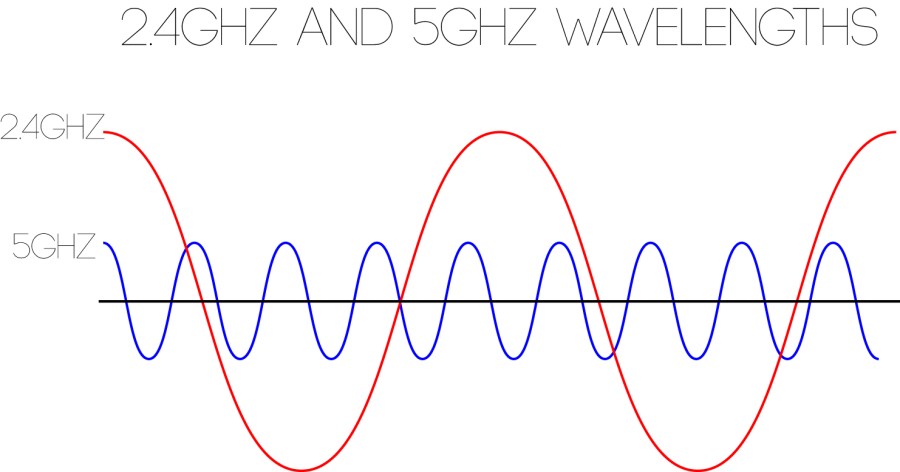

As I mentioned above, different segments of the radio spectrum are called “bands.” A dual band radio can access two of these bands — namely VHF and UHF.

On the other hand, a tri-band radio can access an additional band, HF.

Honestly, if you’ve set up an internet router, you have experience with a dual-band system.

While amateur radio operates on different frequencies than Wi-Fi, both devices use two different sections of the radio spectrum to do their thing.

As a noob, a dual-band radio is all you need!

Duplex vs. Simplex

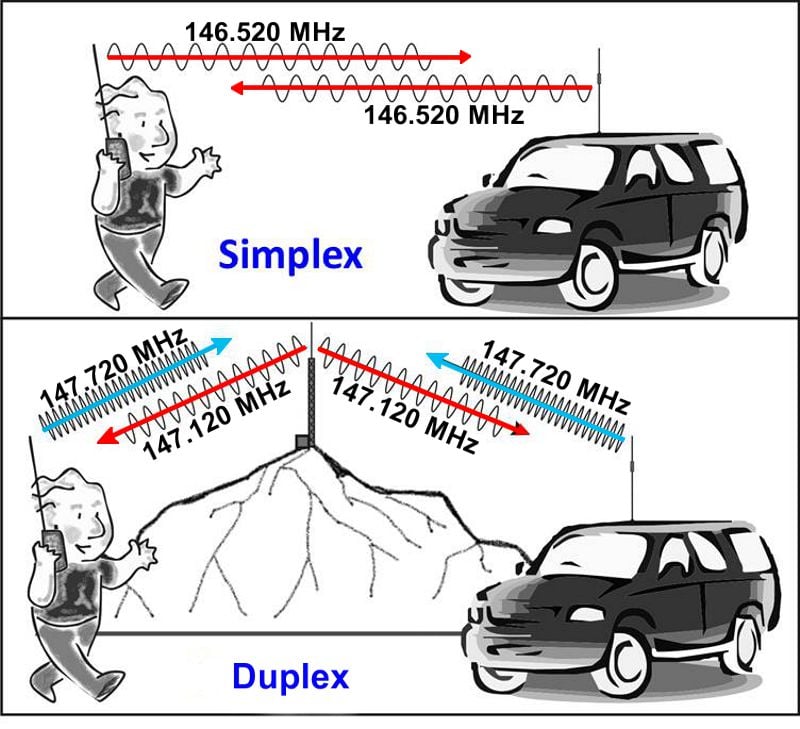

You might also hear the terms “duplex” and “simplex” come up. It is important to know the difference between these terms!

Simplex communication happens when both radios are transmitting and receiving on the same frequency.

It’s simple, you see? Often, this is just radio-to-radio communication.

Duplex is a little more complex. When duplex communication is happening, the radio is tuned to transmit on one frequency and receive on a (usually neighboring) frequency.

This is used very, very often when communicating using repeaters!

When duplex is being used radio-to-radio, it’s worth remembering that one of you will need to reverse which frequency they’re using to broadcast and receive. Otherwise, neither of you will hear anything!

Repeaters

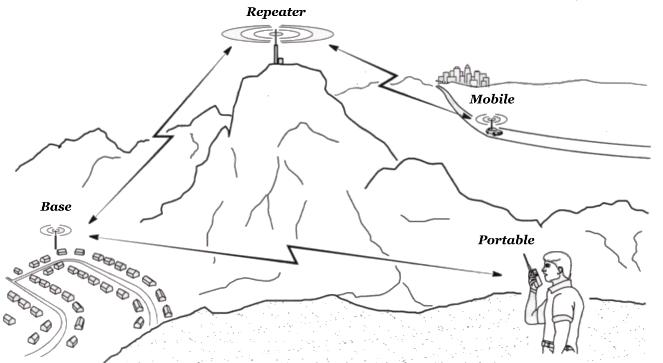

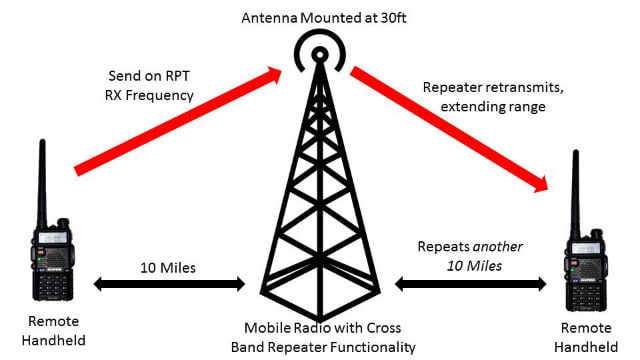

While not every Ham attempts some crazy radio signal bouncing to go around the globe, pretty much every Ham is familiar with their local repeater…or at least, they should be.

If you’re like me, and tend to stick to a battery-powered, handheld radio…you’re not gonna get very far.

Sure, it’s great for talking directly to someone else in your caravan while traveling or keeping tabs on others at a large event, but you probably won’t make it too much further than line-of-sight without a repeater.

Want to know what’s going on in an emergency? Hit up the repeater.

Want to get to know other Hams in your community? Check the repeater.

Need to get a signal out from the affected area in a disaster and call for help? Repeater!

It’s right there in the name — a repeater repeats your signal, but uses its generally high location and significant transmitting power to fling your signal off into the great beyond where others can hear it.

If you live in a mountainous area, a repeater is a must, even to hop the signal short distances.

Like light waves, radio waves tend to like to go in straight lines. An object in the way can block your signal, so instead of going direct, you aim at a repeater and let it help you bend your signal around obstructions.

Every repeater will use dual-band systems to transmit and receive, so you’ll need to know what those frequencies are.

Luckily, there are resources like Repeater Book and CHIRP to help you figure that all out.

Ways to Use Ham Radio

So, you’ve got your basics, and you might still be wondering, “Well, why do I want to go through all the hassle of getting licensed when I can use a cell phone or a walkie-talkie?”

Well, you know that two is one, and one is none, so it’s always a good idea to have layers of redundancy. But also…Ham radio is fun!

Here are a few of the things you can use a Ham radio for!

Emergency Comms

Okay, duh. You know this, but I have to throw it in because I assume that this is what you’re most likely to use it for if you’re…here. On a gun blog.

DXing

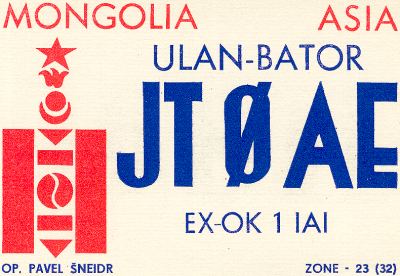

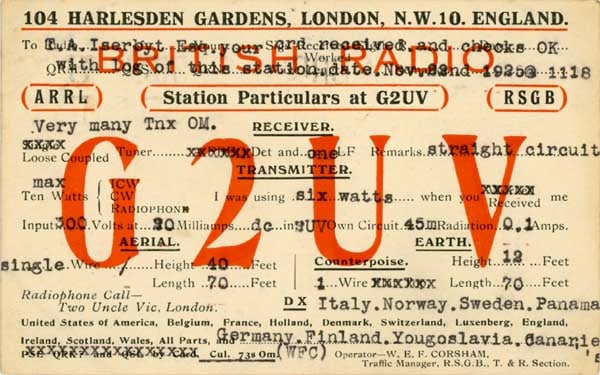

As I mentioned above, DXing (from the shorthand code for “distance”) is the hobby of contacting operators over long distances. Many Ham operators collect postcards as proof of contacts.

Because signals can be so fleeting, some DXs may only consist of swapping call signs — unique, registered identification codes — and then looking up the other person later to pop a card in the mail for them.

Every licensed operator is searchable on a site called QRZ.com (pronounced Q-R-Zed).

Amateur Radio Direction Finding (ARDF)

If you want to combine Ham and hiking, ARDF contests are for you.

They’re also called “radio fox hunting” or “radio orienteering,” which should give you a pretty good idea about what you’re doing.

Competitors use a handheld radio, a topographic map, and some serious skill to find the location of three to five constantly broadcasting, low-powered transmitters and make their way to the finish area in the shortest time

Rapid Deployment of Amateur Radio (RaDAR)

This is a great radio sport to practice making contacts while mobile.

Also known as “Shack in a Sack” or SAIS, it more commonly appears by RaDAR, these days.

Operators have a four-hour window in which to set up their station, make five contacts, pack it all back up, move, and repeat the process.

The competitor with the most contacts at the end of the competition wins.

High-Speed Telegraphy

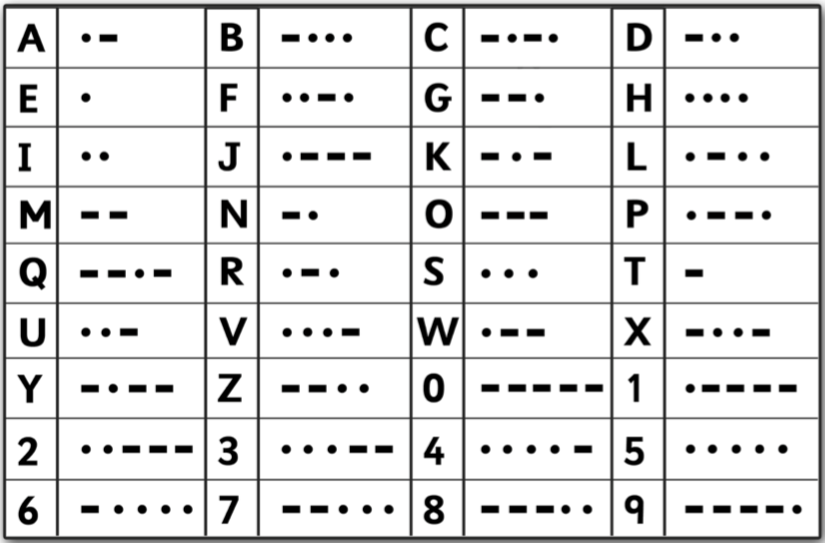

Telegraphy contests involve sending or receiving morse code messages, and as you can imagine — these involve plenty of speed!

Competitors are usually scored on the accuracy of transcriptions and the speed at which they can receive and copy down messages.

Ham Radio’s Role in Emergencies

Ham radio makes for extraordinarily useful comms in emergency situations because there are so many ways you can use it, including radio-to-radio (-to-radio-to-radio…) and as a part of a network, or Ham Net.

Amateur radio has long been used for passing on third-party messages, like emergency communications. It’s a proud tradition of ours.

In fact, the ARRL sprang up in 1914 as a membership group for amateur radio operators who wanted to be part of the chain to pass messages quickly across distances, making them useful for getting information out in the days before mass communication was possible.

In 1935, Amateur Radio Emergency Services (ARES) popped up to provide a more regulated group in which Hams could volunteer their services in emergency-management-related ways.

Later came the Radio Amateur Civil Emergency Service (RACES) in 1952 — an alternative to Civil Defense radio networks, should the need arise.

Heck, up until GPS became more common, Ham operators on their commute played a vital role in the news stations’ traffic alerts!

Why does this all matter?

Because emergency management is a tricky, bureaucratic business.

Amateur radio operators are often some of the first people who can be “on the ground” behind first responders, setting up communication for monitoring conditions, contacting search groups, or scanning for distress signals, and more.

Many, many emergency responders are also Ham operators, because it’s just so dang useful. Members of RACES and ARES may also be registered as emergency/disaster workers under the law, allowing them to stay on and help.

Under normal circumstances, Ham operators cannot communicate with emergency management services and federal operations, such as the National Weather Service, the military, or FEMA. When a state of emergency is declared, these are the FCC regulations that allow any licensed Ham to pitch in:

- 47 CFR §97.111(a)(2) – Essential communication needs and to facilitate relief actions;

- 47 CFR §97.111(a)(3) – With another FCC-regulated service;

- 47 CFR §97.407(d)(1) – Public safety or national defense or security:

- 47 CFR §97.407(d)(2) – Immediate life safety, protection of property, law and order, human suffering/need, combatting of armed attack or sabotage; and

- 47 CFR §97.407(d)(3) – Public information or instructions in civil defense and relief.

Even if you can pitch in, you shouldn’t jump on the band unless you’re a part of the larger response.

Volunteers who aren’t a part of the formal communications network clutter the airwaves and make it harder for those working to do their jobs.

If you want to help out, I recommend registering ahead of time with RACES or ARES.

That doesn’t mean you’re not free to monitor the frequencies used by disaster management and benefit from the information they’re sharing, though!

Just don’t interfere — it’s a crime and can come with some hefty fines.

Licensing

Now, onto how to become a Ham! There’s a little more to it than just poppin’ onto the ‘Zon and ordering a radio for Prime delivery.

In order to use Ham radio, you need proper licensing. (Or at least monitored by a licensed Ham, but let’s just talk about getting licensed.)

Getting your license isn’t all that difficult, but you will need to take a test, and for that, you’ll want to study.

First, let’s talk a little more about the classes of license available, and what they let you do.

License Classes

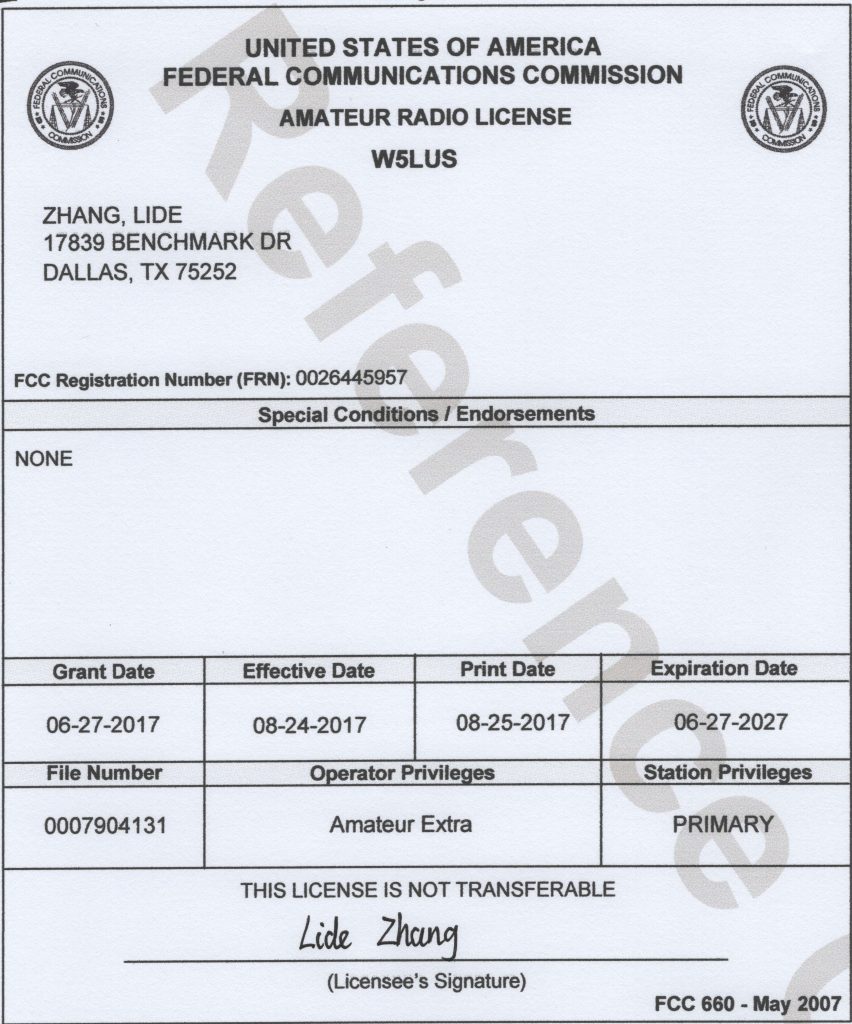

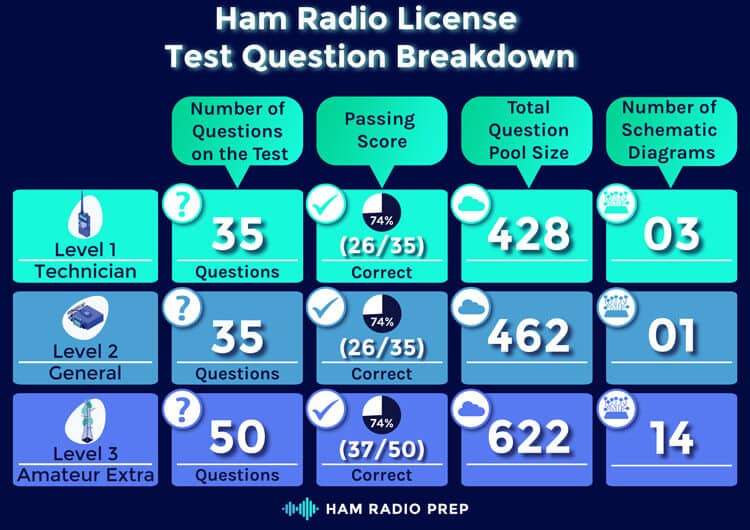

As with other licenses, the higher the class of license you hold, the more privileges you get.

Currently, there are three license classes available:

- Technician

- General

- Amateur Extra

The first license you’ll receive is a Technician license, which grants you the most restrictive use of amateur radio bands.

You can further upgrade to your General class, and then your Amateur Extra class licenses for more privileges. But if you’re doing this for prepping reasons — all you need is your Tech license.

Your Tech license grants you access to every amateur radio frequency above 30 MHz, which means you’ll be able to communicate locally, and generally with other operators in North America.

You also have some limited permissions on HF bands, which allow for international transmitting.

Other Classes

In 2000, the FCC restructured the licensing classes from a total of six classes down to the three I just talked about.

Ultimately, this doesn’t really matter to you. But you should know that these classes did, at one point, exist, and you might run into people that still hold these licenses or mention them.

These classes are sometimes called “grandfathered” classes:

- Novice: Fewer privileges than Technician, mostly centered around morse code use.

- Technician Plus: The same as the modern tech class, but with a modifier indicating that the holder had passed a morse code proficiency test.

- Advanced: Basically the same as the General license, but with a few extra frequency privileges.

The Licensing Test

Now, down to the nitty-gritty! The licensing test…

I know it sounds spooky, but like I said — I passed it at age 11. My brother passed it at age 9 (and then went on to earn his General class license at age 12).

Thousands of scouts, young STEM enthusiasts, and other kids have also passed it. So, you’ve got this!

For your Tech license, you’ll need to answer 35 questions ranging from proper operating practices to radio theory, to regulations.

That means you’ll need to memorize the FCC regulations, how to properly use your radio (such as putting out calls or signing off), and a little bit of electrical engineering, how to build a radio station, and how radios work.

Don’t worry — there’s no math involved.

Most tests are administered by volunteer proctors through the ARRL. Back in the stone ages when I took the test, it was a paper test, but now you can even find them administered online!

To sign up for your test, check out the ARRL’s Test Search tool.

Do I need to know Morse code?

Once upon a time, you needed to know Morse code for a license. The Novice license, which was the lowest class, was exclusively based on Morse code.

As amateur radio moved away from Morse code as the main transmission method, it began disappearing as a requirement from certain classes. Finally, it retired completely in 2007.

So no, you don’t need to know Morse code.

Should you learn it? Heck yes!

It’s a phenomenal, logical system that can be represented visually, auditorily, and as a written language. I never tested for a class that required Morse code, but I still learned it and had lots of fun with it.

Here are some resources to help you learn Morse code, too!

Studying for the Test

You’ll need to prep a little bit for the test — and for using your radio once you’re licensed.

Luckily, it is easy and can even be free to study up!

If you learn best in classes, check out the ARRL’s Class Finder tool to see when classes happen in your area and sign up.

Books more your speed? Check out the ARRL’s recommended guides.

I also recommend checking out Ham Study for online learning — and don’t miss their round-up of resources!

Getting Started

Now that you’re all licensed…it’s time to get started. But what to do first?

Well, in my humble opinion, the first thing you’re going to want to do is shop around for your first radio (or two…or three).

I’ll leave some suggestions down below, but part of the fun is seeing what other people’s rigs look like!

Besides getting your radio, you’re going to want to get on the air and practice. It’s so easy to forget all the intricacies if you don’t regularly operate.

Look around to find your local repeaters and note down their frequencies so you can dial in.

See if there’s a local Ham club in your area, or find an online community to join on social media or forums.

Learn about Field Day and any other radio sport events that might happen around you.

Heck, you might even want to check to see about volunteer-based emergency response groups around you to lend your new skills to.

If you’re planning a space specifically for your Ham pursuits, you should also look into getting that set up and learning more about building your antenna.

Finally, I recommend printing off or memorizing some important information to make your experience better, like emergency radio frequencies and the amateur radio band plan.

What Not to Do

Anything illegal, obviously.

You’ll learn more about that when you study for your test, but some big no-nos include:

- Using Ham for any commercial purpose, including advertising

- Playing music

- Interfering with repeater equipment or communications

- Using explicit language

- Failing to identify yourself by your call sign

- Broadcasting without a license or allowing unlicensed people to use your rig without your supervision

- Use amateur radio to coordinate or commit criminal acts

- Operating outside your band or power permissions

Additionally, there are some etiquette protocols you should follow, especially if you don’t want to be “that guy” on your local repeater. Here are a few tips:

- When you change to a new frequency, listen in for a minute to make sure it isn’t in use.

- Ask if a frequency is open by identifying yourself and asking.

- Identifying yourself often, whenever asked, and when joining in on a new conversation.

- Never, ever, ever keying your mic or hitting your Push-to-Talk button when someone else is speaking or when not speaking yourself, because it will broadcast a noise.

- Not speaking over others.

- Checking in every so often when monitoring a frequency to identify yourself and announce that you are monitoring — Ham know their transmissions are public, but it’s polite to let them know you’re listening.

- Speaking clearly, slowly, and at a reasonable volume.

If you’re new, that can be a lot to remember. It’s easy to get excited and jump into a conversation. Sometimes, you will make mistakes.

Most Hams are pretty nice, though, and like seeing newcomers to the hobby.

We know it’s endangered and we want to show you the ropes. So, it’s worth being humble and asking lots of questions rather than assuming and getting it wrong.

You’ll see that most operators will want to talk your ear off if you do ask a question, so ask!

Best Ham Radios for Beginners

Now, let’s look at some radios I recommend to get started!

1. Baofeng UV-5R

Listen, if you’re going to pick up a radio from a long-dead survivalist who fell prey to zombies — it’s pretty much guaranteed to be a Baofeng UV-5R.

These little radios are freakin’ everywhere because they’re $25 a pop. At that price, you can outfit a whole squad for a couple of bennies.

Which, in my opinion, makes them a phenomenal first radio for a budding Ham.

Up is pretty much the only direction you can go from a Baofeng, but that’s not to say they’re bad radios.

Baofengs may have a name and a price tag that screams “Wish.com” but they’re actually adept, handy little radios with a number of features that make them seem much more expensive than they are — like a built-in flashlight.

It provides you with 4W of transmitting power, which is enough for most short-range applications (and hitting a nearby repeater).

I keep one on hand as a back-up radio in my car.

It’s never my first choice, but it’s always on hand. And it’s cheap enough that I’ll be angrier about my car window than the radio if someone wants to snatch it.

-

25% off all OAKLEY products - OAKLEY25

Copied! Visit Merchant

Want to learn more about this iconic Ham radio? Pop on over to How to Use a Baofeng UV-5R, where Aden shows you all the ins and outs of this lil guy!

2. Yaesu FT-65R

If you’re getting into amateur radio, you’re going to notice that you see a lot of Yaesu products.

And that’s because Yaesu is one of the best manufacturers of Ham radios out there. I trust them a lot.

The Yaesu FT-65R is a great, feature-rich handheld radio that won’t overwhelm a beginner. But it will give you what you need in a good radio.

I would rather recommend the FT-60R, but that one can be a little hard to find at times.

The FT-65R is still a great radio, though, offering 5W of transmitting power, which, again, is enough for a handheld.

It has an IP54 rating and the MIL-810-C,D and E standards for dust and water protection. In short, it’s pro-grade rugged.

You shouldn’t have to worry too much about it.

It uses a 1950 mAh Li-Ion battery pack, which gives you about nine hours of battery life per charge.

You can also get an upgraded pack that gives you 11.5 hours of charge, which is a major plus when it comes to “oh no, zombies ate all my neighbors” situations.

I also appreciate that it comes with a 3.5-hour rapid charger.

Another feature I think you’ll appreciate is that it is computer programmable. So, you can use software and a programming cable to handle plugging in all your channels that you want it to remember.

Prices accurate at time of writing

Prices accurate at time of writing

-

25% off all OAKLEY products - OAKLEY25

Copied! Visit Merchant

Have you used the Yaesu FT-65R? If so, let us know by rating it below!

3. Retevis RT82

The Retrevis RT82 is a budget-friendly option but with enough features that make it a stand out.

In addition to being water- and dust-proof (IP67 grade weatherproofing), it has GPS capability and a really cool “lone worker” feature that can send out a signal if you haven’t transmitted for a certain amount of time.

It functions in analog mode, which is your traditional Ham radio, but it also works in digital mode. This allows it to use GPS and send text messages to other digital radios.

So, this setup brings more options than just a straight Ham radio.

Not only does it have great squelch for clear audio, it also is computer programmable and comes with the programming cable. Which is not something you can say about every radio!

Prices accurate at time of writing

Prices accurate at time of writing

-

25% off all OAKLEY products - OAKLEY25

Copied! Visit Merchant

4. Yaesu VX-6R

Another Yaesu? You should have seen this coming when I told you that Yaesu’s were the Ham brand!

The Yaesu VX-6R has been around since 2005, which tells you a lot — both that it’s a great radio, and that Hams are a little fuddy-duddy when it comes to upgrades.

But really the reason the VX-6R has such staying power? Because it’s simple to use and offers tri-band (as opposed to dual-band) functionality.

Oh, and did I mention it comes in a super rugged and waterproof design? ‘Cuz yeah.

You have 10 channels of memory storage on a one-touch button, so you can pull up your favorite frequencies quickly.

It also can tap into the Emergency Automatic Identification (EAI) system, has a smart-scanning feature that will look for signals for you, and lets you monitor many emergency channels.

Powered by a 1400 mAh Li-Ion battery, it provides a battery-saving auto-off and Wake Up feature, so that your charge lasts longer.

Prices accurate at time of writing

Prices accurate at time of writing

-

25% off all OAKLEY products - OAKLEY25

Copied! Visit Merchant

Conclusion

Ham radio is an important tool essential in any modern prepper’s toolbox.

From handling emergencies, to staving off the zombie apocalypse, or just meeting new friends, ham radio offers a great way to stay prepared and enjoy some fun.

So, anyways…hopefully your eyes aren’t glazed over after all that and you have a good idea of your next steps if you want to become a Ham operator!

Whether you want to learn how to use amateur radio for prepping reasons only, or you’re interested in getting into the hobby — welcome! I hope you have a ton of fun with it.

KI6DIF, signing off. Clear on your final!

What aspects of amateur radio did you want to learn more about? Let us know in the comments! To learn about other radio systems, check out our Guide to 2-Way Radios.

2 Leave a Reply

I am just getting into HAM radio. My first step was to read up on the subject. Your info and the LINKS you provide are very helpful!

I'm going to jump in... hands first, and get involved. It sounds like the way to go, especially since HAM will be indispensable when (not IF) the Feces hits the spinning blades!?

Thank you for the short and concise article for us "Newbies"!

Allison, is that your natural hair color? Nice! Very unique!

Great round up of information on HAM radio communications possibilities. Thanks Allison.

Jack

KL7AZ

PS Hope you also keep a couple radios in a Faraday cage or enclosure.