The Quest for the All-In-One Military Firearm

Most historians point to the Korean conflict as a change point in defining optimal firepower in battle and in turn, what was then termed the modern battlefield. U.S. infantry soldiers armed with World War II-era semi-automatic M1 Garands and M1 carbines quickly found themselves both outmanned and outgunned.

- An M1 semi-automatic rifle weighed 9½ pounds, was over 43 inches long and relied on en bloc eight-round clips of .30-06 ammo. It was powerful and accurate but no match for sheer numbers of enemy.

- An M1 semi-automatic carbine was lighter—just under 6 pounds—with a 15-round clip of .30-caliber carbine. The M2 carbine offered selective fire and a 30-round banana clip. However, neither was able to stop a swarming enemy.

Rethinking Effective Range and Caliber

Researchers at Aberdeen Proving Ground’s Ballistics Research Laboratories (BRL) had been analyzing the lethality of ammunition, looking at mass and velocity since 1938. This may seem like dry stuff now, but then, these were radical ideas.

- The range of rifle fire rarely exceeded 500 yards.

- Rifle fire was most effective at about 120 yards or less.

- The most lethal bullet would be high-velocity but small-caliber.

- Military rifles were effective only at 300 yards or less.

- Most kills happened at less than 100 yards.

- Small-caliber ammunition best performed the task.

- Soldiers aimed only the first of their eight M1 rounds.

- Despite aim, wounds inflicted in battle were not concentrated in targeted body parts but instead were surprisingly randomly distributed.

M14—The First Try

At first, the story seems simple enough. Reluctant to accept the idea of small-caliber efficiency, the Army basically remade the M1 into the M14 by attempting to make it fully automatic.

AR Is for ArmaLite

In the 1950s, the Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation decided to branch out into small arms. By 1954, ArmaLite was the start-up division, intent on designing and manufacturing a new generation of small arms from its base in Hollywood, California. Its first almost-sale was its AR-5, a .22-caliber bolt-action rifle designed for the Air Force. It weighed less than 3 pounds and could be broken apart to store the barrel and works in the plastic stock. It was to be the MA-1, but the sales never really happened.

W Is for Wyman

Meanwhile, General Willard Wyman, a West Point graduate turned four-star Commanding General of Continental Army Command (CONARC), was impressed with ArmaLite’s AR-10. In fact, he was so impressed that in 1957, he visited Eugene Stoner, invited him to try again and offered funding in exchange for proprietary rights to create the AR-15. Wyman is a name worth knowing in this context because he integrated the Trainfire program and its then-novel ideas of modern warfare—lots of ammo at terrifyingly close ranges—into the Army’s basic training. He even requested delays on the T44 decision to allow time for the AR-15 under development, but it was not to be.

ArmaLite’s AR-15

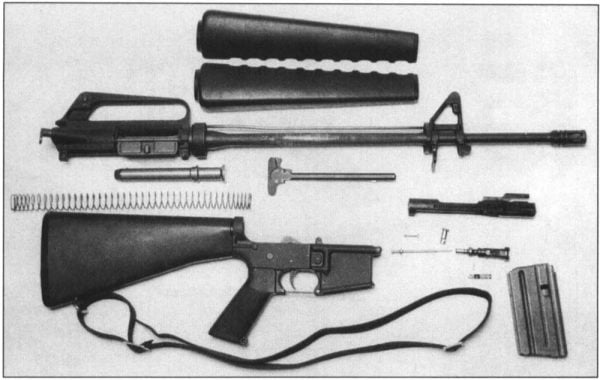

So, you ask, what were they testing? Stoner’s first AR-15 weighed just 6 pounds or so and was 37½ inches long. The hand guard around the barrel was Bakelite, and a three-pronged flash suppressor graced the tip of the skinny barrel.

The Politics of Firearms

New ideas can be problematic, and the AR-15 was no exception. In addition to General Wyman, several other personalities played significant roles in the M16’s path to service. Dr. Frederick Carten, head of the Army Ordnance Corps, wasn’t exactly enthusiastic about a small-caliber weapon made of plastic that felt—and looked—like a toy.

Colt Owns the AR-15

The AR-15’s future was looking grim. Fairchild was unhappy with its nearly million-and-a-half-dollar investment. By the end of 1958, Fairchild had claimed losses well over $17 million. On February 19, 1959, Fairchild sold the exclusive manufacturing and merchandising rights for the AR-15 to Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company for $75,000 and a 4.5-percent royalty on future sales. In addition, Colt agreed to pay Cooper-MacDonald—a marketing group with ties in Southeast Asia—$250,000 and a 1-percent royalty per weapon as a finder’s fee.

ARPA, AGILE and the AR-15

In 1958, the Defense Department had created the Advanced Research Projects Agency — DARPA — to supply the military with game-changing technology. You may be familiar with DARPA from their work with Boston Dynamics on the Spot project:The McNamara Factor

The M16’s story simply cannot be told without a nod to Kennedy’s Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara. He was aware of conflicting assessments of the AR-15 and the Ordnance Corps’ decided lack of impartiality. As a former Ford executive versed in assembly-line efficiency, he also was an avid proponent of having one universal weapon for all services.

- 50,000 to 100,000 AR-15s for special forces, airborne and air assault units and

- “a sufficient number” of M14s to provide infantry squads with “automatic rifle capability.”

Trial by Fire

By 1963, the U.S. had between 15,000 and 21,000 advisers and special forces troops in Vietnam. So far, the approach had been special ops, paramilitary training, and insurgency. However, the North was determined to expand its power base, and the South was ever more reliant on U.S. support as the conflict intensified. When the USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy were “attacked” in the Gulf of Tonkin in August of 1964, Congress quickly passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution—giving President Johnson unilateral power to conduct military operations in Southeast Asia. It wouldn’t be until 40 years later that the truth of the USS Maddox incident would come to light. In short, the “attack” never happened.

Failure To Extract

Numerous investigations began—some within Colt itself while others began within the Marines, Army and even Congress. Some—including generals—claimed nothing was wrong with the M16, going as far as to point the finger of blame and inadequacy at the soldiers themselves.

- The ball powder burned too fast, fouling the chamber as it pushed the cyclic rate from 700 to 800 rounds per minute to more like 1,000. It was also moisture-sensitive, swelling or even bursting cartridges in tropical humidity.

- The seemingly cost-saving decision not to chrome-plate the chamber exacerbated the problem as the resulting rust, pitting and corrosion increased the likelihood of a malfunction.

- Lighter firing pins replaced the original, heavier ones that were prone to unintentional slam firing.

- Weights and spacers added to the buffer eliminated the problem of cartridges struck but not fired and helped to slow the cyclic rate.

- Parts like the bolt and disconnector were strengthened to better withstand the high velocities and impacts involved.

- The more expensive 7075 T6 aluminum that Stoner originally intended to use for the receivers replaced the inferior 6061 T6 aluminum that corroded over time.

Ammunition Revisited

Throughout the M16’s development, ammunition played a key role, and that didn’t stop in 1968. In 1953, the 7.62×51mm NATO rifle cartridge—the round that both the M1 and Eugene Stoner’s original AR-10 fired—became the first standard NATO rifle cartridge. This was a large part of why Army Ordnance proved so resistant to Stoner’s AR-15. To achieve the performance levels required for the AR-15, Stoner worked with Sierra Bullet’s Frank Snow, Remington and Robert Hutton to devise the .222 Special, which became the .223 Remington and eventually “Cartridge, 5.56mm Ball, M193.”

The M16A2

- the option of a three-round burst rather than full automatic selection,

- a heavier barrel,

- rifling of one turn per every 7 inches,

- a muzzle brake with a solid bottom rather than a vented flash suppressor,

- a square front sight post,

- canted slip ring for easier hand-guard removal,

- a brass deflector,

- a redesigned rear sight allowing adjustments for windage and elevation, and

- a button-style forward assist.

- seen action in conflicts like Granada, Haiti, Panama, Bosnia, Somalia and Iraq;

- gone through changes and iterations, from carbine Commandos to the M16A2; and

- served as inspiration for its replacement—the M4.

19 Leave a Reply

Thank you for your service.

As someone who appreciates mechanical poetry, I equate the AR in the same vein as a sewing machine, moderate complexity executed with simplistic efficiency.

Like many others my introduction to the m16 was basic training.

My initial reaction, never having seen one before was shock... "What the hell is this? Are you serious?"

Then I shouldered it & thought... "maybe... this could work. Then, as if I had a choice, decided to give it a chance."

Once I fired it & became intimately familiar with it, I was in love.

This was the era when the sabotage & bugs had just been resolved.

I NEVER had a single issue.

Once in Vietnam, I was issued the AR-7 (remained with the aircraft) and the early carbine.

I wasn't fond of the carbine so I "acquired" a standard rifle. I believe it was a 603/604. Basically an m16a1 without a forward assist.

It treated me extremely well.

My "two cents worth" on the evolution of the AR platform as follows...

Like John Browning, Eugene Stoner was a genius.

Against all odds he gave us a near perfect design.

Personally I feel the A1 version was the peak.

I never found a need for the forward assist so I'm not commenting on it beyond this.

After the A1, the only viable improvements I saw were the delta ring and the three round burst. In a perfect world, it should be a 4 position selector.

I prefer the trapdoor buttstock but don't see the need for the added length of the A2 stock.

The round forward grip still bothers me... but I get it.

The easily adjustable rear sight of the A2 was a really bad idea!

It's simple to adjust windage & elevation without adjusting your sights! Changing your zero, in battle is just stupid! Conditions change & it's impossible to get it back to zero on the battlefield.

Beyond that, all that's been accomplished over the years is to ignore the initial criteria of maximum weight etc.

I've found that "most" veterans prefer what they were issued. I know I do.

Today's modern civilian configurations bother me far more than they should.

I'll stick with the 604 or the M16a1.

In 1967 I was with H&S Co Armory, 1st Bn. 9th Marines. We were issued XM16E1s and our M14s were turned in. I witnessed the hundreds of malfunctions and jammed rifles of the KIAs and WIAs of my battalion. I remember days with us (armorers), working feverously, trying to repair these weapons. They were trash and should of never been issued to ANY U.S. Serviceman. Until I die, I'll remember this.

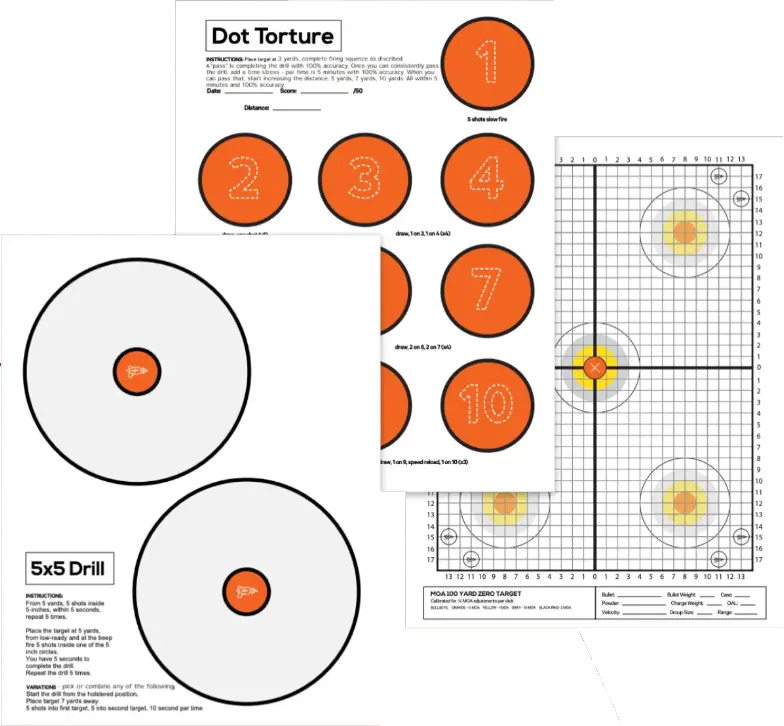

To state: "that infantry troops often had insufficient training and experience with the M16 prior to having to use it." is total bull shit. Basic training consisted of physical training, hand to hand combat and weapons training. Granted some had troubles hitting the 300 yard targets while a few of us could impact out to 500 yards. We had to work on tightening up our grouping. Zeroing in our sights and quickly tearing down, cleaning and reassembling our weapon. My M16 saved my life and allowed me to come back home.

Excellent article!! Well researched and once more shows how many REMF's are still gumming up decision making.

Great history lesson, thanks. I carried the M-16 in the Air Force, late 70s and wondered why the Army/Marines would want to further jam a weapon with forword assist, but thats just my A.F. thinking. ;)

Outstanding! I read many times different parts of the story with maybe some small differences here and there (like Stoner jump in Armalite) but overall this was a heck of piece, interesting and entertaining, full of all details to understand ALL the whole story. THANKS!!

I trained with the M16 while on the firing range during Basic Training in 1970 at Ft. Dix, N.J. My M16 jammed a couple of times and I worried about using this weapon in combat situations. Felt too much like a toy and not very reliable.

Lots of miss information here. For example saying M16, then differentiating the M16A1 from it. the rifle before the M16A1 would be a XM16E1. Not only that, the rifle being called an M16 isn't even an XM16E1! It is a colt model 601, the first rifles given to air-force and select special forces units! Then they go on to say 1:7 twist was new in the M16A2, when it was actually a change made between the XM16E1 and M16A1. I promise that there are many more mistakes like that here and advise you to get info on the evolution of the rifle elsewhere.

That Marine in the A2 pic appears to be wearing Army ACUs

he also has an air national guard sticker on the stock of the rifle.

I agree some of his background information was not exact on however, the piece was about the basic history of the politics that the AR went through. If our government would of stepped aside and allowed the early engineers to do what they do without the political asswipes getting in their way, allot more of our soldiers would of come home in the early years of the South East Asia conflicts and the M16 would of never been. It would of been the AR-15 that would of been much closer to the M16A2 as our rifle choice at the onset of the Vietnam conflict. Our government always seems to forget that cheap means cheap like the cheap vehicles we have used in Afghanistan and Iraq without sufficient armor to protect from IED and RPG. More of my brother have been killed and permanently injured as a result of not spending the money to improve armor on our logistic and light duty vehicles. Also, better head and ear protection so that BTI can be reduced. It's always been the politics and the article was about that to me.

Get a grip. Some arbitrary mistakes with regards to the names of various models of the weapon or esoteric technical details of a rifle that has a frankly complex historical evolution hardly constitutes as “lots of miss information (sic - it’s misinformation, the irony….)”.

As a Brit who has always had a passing interest in firearms, I found this article incredibly informative giving me an excellent, in-depth account of the history of the weapon(s) written in a very engaging and readable style. So credit to the author - he can be forgiven for a few minor errors which didn’t take anything away from my experience of reading the piece. By all means correct him but your snark suggests to me that you are a rather rude individual indeed.

Man, this is a great historical review article. My very first introduction to the M16 came during JROTC in high school in the mid ‘70s. Didn’t have to learn to shoot them (firing pins removed) but we did have to study military history and battle tactics. Oh and we had to learn to completely disassemble one in under 30 seconds, clean it and reassemble it in 25 seconds. And whenever we were inspected in formation the rifle was assessed for cleanliness and function. At least one year of JROTC, with weapons training, was required by all male students for graduation; and you know what? No one was ever injured on campus and none of our graduates were ever implicated in what we call today - gun crime.

Our HS ROTC program did sponsor a school rifle team where we did get to shoot an M16 - just for the experience - but shot competitively with very heavy all wooden and steel furniture competition designed rifles in .22LR. I didn’t go on to college ROTC but I did shoot on the college rifle team.

Excellent article, thank you for putting this information together!

Agree 100%

Good article over all. Learned a lot.

Suggest you re-visit your historical account of "USS Maddox and USS Turner Joy were attacked in the Gulf of Tonkin in August of 1964" .... because (as later revealed) it never happened.

Thx

Poor communication for the sake of brevity on our part, although it would take 40 years after the fact for us to find that the attack did not occur - at the time it was believed to be real and lead to the resolution being passed that allowed President Johnson to increase American presence in Vietnam.

I'll edit it a bit to make it more clear!