Perhaps no other survival environment is filled with as much myth and guesswork as survival at sea.

So just how do you survive at sea?

Assuming you started on a boat, we’ll walk you through what the experts say are the best methods to stay alive while adrift at sea.

And we’ll take a look at a few survival stories to see just how others made it out alive.

So keep reading to learn more about how to stay alive in the open water.

Table of Contents

Loading…

When Do You Abandon Ship?

A humpback whale breached, causing significant damage to the hull of your ship (it happens).

Now your ship is taking on water fast, and you’re out alone in the open ocean. Unsure of what to do, you know one thing…there’s zero chance of repairing your boat.

The only question left — when do I take to the lifeboat?

A general rule of thumb amongst sailors is to not abandon the ship until the water has reached waist level.

Anything before that time is likely premature.

As the old sailor’s adage goes, “The best lifeboat you can have is your ship.”

For starters, your ship offers a much higher level of buoyancy than your lifeboat. This means it tolerates rougher conditions that would otherwise capsize your lifeboat.

A damaged ship – even though largely swamped – can still float/travel significant distances, as has been evidenced by thousands of occurrences throughout history.

So, stay aboard your ship if you can. But also understand that you need to be ready to bail if it’s no longer safe to stay.

Life Aboard a Lifeboat

Let’s be honest. This is going to suck. There’s no way around it. Understand that and, like an Army Ranger, embrace the suck.

While life is going to feel difficult, there are several things you can do to make it just a little more comfortable.

Not to mention a couple of things to improve your chances of making it through in one piece (rather than little bite-sized pieces for sharks).

Shelter

For starters, rig up some system of shade.

As you’ve probably imagined, drinkable water will be a big issue. You will dehydrate after an extended period.

Who dehydrates quicker, though, the Arizona roofer or the stonemason in the shade? The guy in the sun, right?

The same applies to a lifeboat. You’ll dehydrate like a raisin. So, find a way to rig up some shade or keep yourself out of the sun.

Water

Hand in hand with your need for shelter is the need to gather as much water as possible.

You have three ways of doing this — collecting rain, solar stills, and through a couple of different food sources.

Collecting Rain

Make this a priority while at sea. You never know when the next rainfall will come – two weeks from now, maybe?

As a result, collect as much rain as possible when you can, as this will serve as your largest source of fresh water.

But make sure to prepare for how to accomplish this well before it actually rains.

Any container you have should be prepped for this function.

Figure out ways to rig tarps, plastic, space blankets, or other types of rain catchment devices to funnel as much rain as possible into containers.

Three Mexican fishermen spent nine months adrift in 2006, Jose Alvarenga spent 438 days lost at sea, and Steven Callahan spent 76 days lost at sea. How did they make it?

All of them collected rain to stay alive.

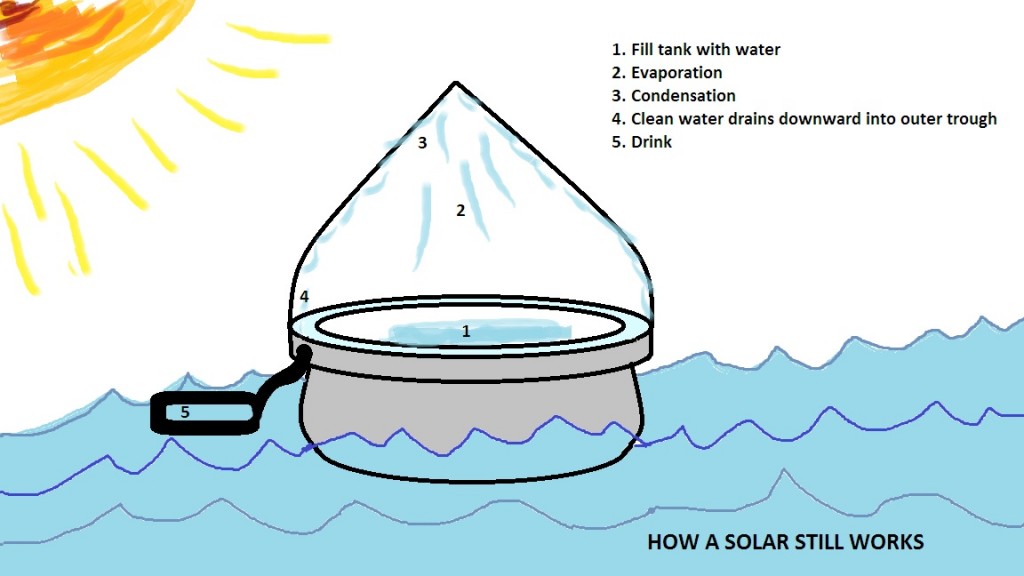

Solar Stills

Steven Callahan spent 76 days swept at sea aboard a small inflatable raft he named the Rubber Ducky III.

While rain was one of his main freshwater sources, he also relied heavily upon an old military surplus solar still.

As I mentioned, you have no means of determining when the next rainfall will come. So, you’re going to bake in the sun all day long. Your water needs will be intense.

Collecting as much as you can only makes sense.

That’s why – if you spend any significant amount of time at sea whatsoever – I highly recommend investing in at least one solar still by Landfall.

While they come in around $250, that’s a small price to pay if you’ve been stranded at sea for over a week.

If you don’t have a commercially available option, you can try to make one, but it’s most certainly not a foolproof option.

Callahan attempted that with a Tupperware box, tape, plastic, and several empty cans but was never able to get a tight enough seal to be successful in his attempts.

And this was a man who made a workable sextant out of three pencils and some twine — he was by no means an idiot. He just didn’t have what he needed, and you likely won’t either.

Fish

Believe it or not, fish can act as a source of freshwater. You’ll have to engage in some X–Files type behavior to get it, though.

For starters, fisheyes are over 90% water. While a fisheye isn’t that big, it is at least something.

If you snap open the fish’s spine, there’s a bit of freshwater that will flow out as well. Tilt it into your mouth and slurp it up.

What to Eat Though?

While you need to limit your eating in times of no water — digestion sucks up a lot of water — you can’t just let yourself starve to death either.

Outside of whatever stores you could bring with you on the lifeboat, prepare to eat a lot of seafood.

Little fish will be attracted to the shade your boat creates. So, if possible, you should try to catch as many of them as you can. Use the guts of the first one you catch as bait for the others.

At nighttime, you can attract more with a flashlight.

Seagulls can be eaten as well. This was one of the main food sources of Jose Alvarenga, along with turtle meat and turtle blood. Though it’s not palatable, it’s better than starving.

If you can scoop up some seaweed, there’s a good chance little shrimps and crabs are going to be hanging on it. You can eat them too.

The seaweed itself can be eaten, but it’s best to cook it first. Otherwise, it can be kind of rough on your gut to digest (read: you’ll have a weird stomach and poop like a champ).

“What if I catch a shark, though?”

Yeah, that could potentially be a problem.

If it’s a big shark, just cut the line. It’s not worth dying from blood loss.

If it’s a little shark, lift it out of the water just enough (not with your hands) and then beat the life out of it with a stick.

Make 100% sure that thing is dead before you bring it into the boat with you. If it is, you now have extra food!

What If You Get Swept Overboard?

You can do things to increase your survivability but try to avoid ending up in this type of situation if you can (duh).

That all said, if a big wave does leave you a long way off from your boat, here’s what you should do:

Find something floatable to hang onto.

Treading water for long periods is hard. A buoy, life preservers, scrap of wood – just find something – and hang on for dear life.

Float on your back

This only works in calm water, but it can most certainly keep you from drowning from exhaustion.

Do the dead man’s float

If the water is rougher, this will be a much better option than floating on your back. Lift your head when you need to breathe, and then go back to floating like a corpse.

Hopefully, this will help keep you from doing the real deal.

Where To Go on a Lifeboat?

This one will depend on your current capabilities.

Some lifeboats are left to the mercy of the winds and currents (e.g., the Rubber Ducky III), while other lifeboats offer some form of rudimentary steering faculties.

If you could get an SOS message out via your radio before sinking, or you’re in a heavily traveled shipping lane, then your best bet is to stay as close to the wreck site as possible for 72 hours.

This is where search-and-rescue teams are going to begin and radiate out from.

If you couldn’t get out a mayday message and you’re in a less-traveled area, however, your best bet is to use your initial strength reserves to head in the direction of the closest land.

Signs You May Be Approaching Land

Mental mindset is key to surviving a disaster situation, and hope is often a large piece of the puzzle.

Understanding how to read signs of impending land can help you cultivate that hope. Here are some signs land is close.

Cumulus clouds — Typically, these form over land. If you see them in an otherwise clear sky, land’s likely the cause.

Birds flying overhead — Seagulls and pelicans rarely fly over 100 miles away from shore. If you see them, that’s a fantastic sign! They typically head out to sea before noon and head back to shore in the evening.

Driftwood floats near you — While perhaps the least predictive of the three, driftwood and other floating debris typically hang out near coastal waters.

About Your Emergency Radio

Your lifeboat will probably have some form of emergency radio on board. You’ll want to use it to signal for help.

However, you’re only going to have a limited battery supply, so be prudent in using it. Your radio likely operates within the VHF spectrum, meaning you’ll have a range of somewhere around 20 miles.

If you see a boat, land, a plane…use your radio. Save the radio for when you believe you’re most likely to reach somebody.

Aside from the radio, you’ll likely have an emergency position indicating a radio beacon.

This will broadcast your GPS coordinates to a wider range, often much further than a marine band radio.

Conclusion

There’s no way around it – surviving at sea is rough. However, it’s possible to stay alive at sea with the right tools and knowledge.

If you’re interested in learning more about past survivors, I recommend reading Steven Callahan’s Adrift or Tami Oldham’s Red Sky in Mourning.

Both of them spent well over a month at sea, fighting against the elements, hopelessness, thirst, and starvation to survive. Their stories are powerful, and they offer much to learn.

What are your thoughts? Is there other gear out there you recommend for sea survival? Let us know in the comments below! Ready for more survival content? Check out our guides on beating the odds against Nukes, EMPs, Wildfires, and Tornadoes.

5 Leave a Reply

Charles left some great high level information. I am a life long mariner, sea captain, and owner of a training facility as well as an avid reader of Pew Pew Tactical. I'd love to add more information outside of a random comment from time to time, so to give additional information for anyone who ends up in this position.

I have not faced this but its a huge fear. People can take heart in something. In the Fastnet Race of 1979 in which the storm killed many sailors due to drowning, most of the abandoned boats which lead to the sailors deaths were found intact a few days later. A boat can stay afloat with 50% of its air space (displacement) flooded. People jump ship too early in fear of sinking. Second, outfit the lifeboat/dinghy in advance -- water, sextant (and know how to use it), some charts, food, blanket (the sea is freezing at night), tarp, first aid, kinetic flashlight, collapsible fishing rod and line/hooks/bait, EPIRB (in-date!), a makeshift sail, signal mirror. Most people dont know that aviation and maritime law dictates that when seeing a signal, planes and ships must investigate. A credit card mirror can be seen 50 miles, a foot square mirror can be seen 300 miles. There is abundant info online about prep for a lifeboat, read it. As to boats taking on water, anticipate the need for the largest bilge pump you can afford.

Great information! Very simple and high level. To expand on your points a bit, the 50% air space you speak of is the reserve buoyancy that we count on to help calculate intact as well as damage stability to make a decision to abandon or not. NEVER abandon a vessel that doesn't have the continued potential to abandon you first. As far as a sextant, its becoming increasingly rare to find laypersons who understand celestial navigation completely. A compass and small basic chart (which you mentioned) would serve a bit better as well as an understanding of a general idea of where one is at, to help with potential rescue in the "Golden Day" (The first 24 hours after an incident). The rest of your list is ABSOLUTELY critical (especially the EPIRB).

Also, you are absolutely correct that not only federal law here in the U.S. as well as globally requires vessels to investigate potential distress signals.

As far as a signal mirror, I've seen a polished hubcap (Haitian raft had this) 17 miles away, VERY CLEARLY. The 300 mile visibility part, I'm going to have to disagree with in the terms of maritime. This may be true with the aviation world, which I will be researching because this is very cool information that I'd like to incorporate in my training classes.

I never go further in the ocean than I can swim back.

Haha, I'm a fan.