Do you know who had a real penchant for naming drills?

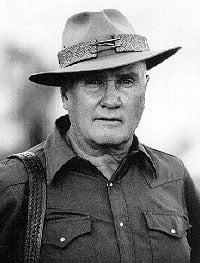

Jeff Cooper, founder of the Modern Technique, IPSC, the ole Scout rifle, and more.

Well, the man could name a drill.

We got the Dozier Drill, the El Presidente, and of course, the Mozambique Drill.

All three of these are quite famous in the world of firearms, but the Mozambique Drill gained recognition even outside the world of firearms.

“Two to the chest, and one to the head” is a mantra reflected by a variety of pop culture sources…and it comes from the Mozambique Drill.

Michael Mann, director of Heat and Collateral, made the Mozambique Drill a signature of his films.

So, what’s the big deal with this drill? Where did it come from? Most of all, how can you do this drill at home?

Well, let’s dive in and figure it out.

Table of Contents

Loading…

Breaking the Drill Down

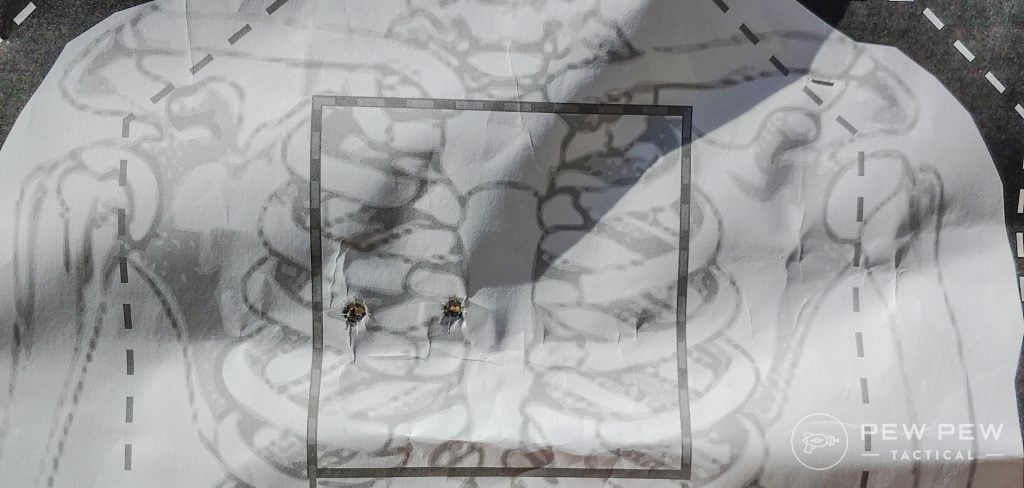

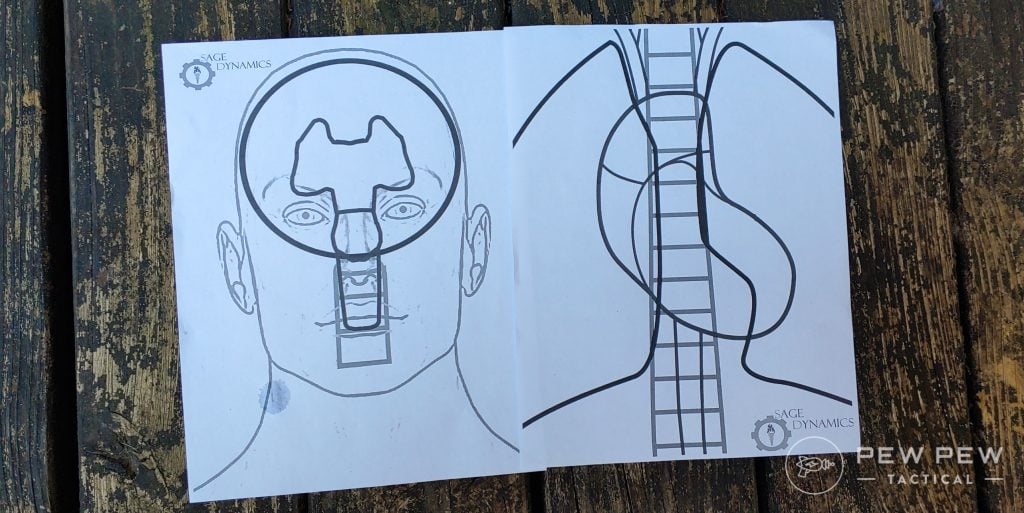

The Mozambique Drill, also known as the Failure to Stop Drill, is very simple. You’ll need a man-sized target with a distinguished head and torso — preferably a chest and head target.

You can fire this drill from various distances, with 7-yards serving as a great starting point.

Shooters begin the drill at the low ready or with a firearm holstered, depending on skill level.

Traditionally it’s fired from a holstered situation, but it’s not required.

As you can guess, the drill involves firing two to the chest and one to the head. That’s true, but let’s break that down a little more.

You can start the drill with a double-tap to the chest of the target.

Just so we’re clear, a double-tap is two rounds fired in rapid succession — two shots with a single sight picture. On the other hand, a controlled pair is two shots with two sight pictures.

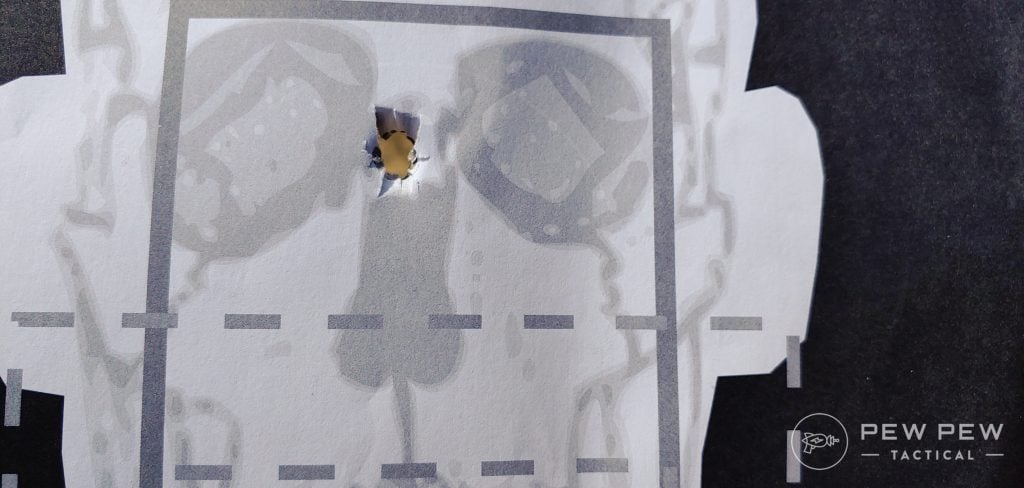

After the double-tap, the shooter transitions to the head and takes a well-aimed headshot. While speed is always critical, accuracy is more important for the final shot.

The idea is rather simple.

The two shots to the chest stun and wound the bad guy, preventing him from attacking you. This buys you time to take a well-aimed headshot at the bad guy.

What in the Mozambique

Where does the Mozambique Drill come from? Why is it named as such? Well, it all starts with a mercenary named Mike Rousseau.

Mike Rousseau served in numerous wars, including the Mozambican War for Independence.

The story goes that Rousseau was fighting at an airport. He rounded a corner and came face to face with an AK-wielding combatant.

He raised his Browning Hi-Power and launched two 9mm rounds into the combatant’s chest. But the man failed to fall or stop, and a wounded man with an AK-47 is still a very dangerous man.

Rousseau wasted no time, firing a third and final shot into the combatant. The round was aimed at his head but went through the neck, severing his spinal cord.

Rousseau told the story to Cooper, who absorbed its lessons and created the Mozambique Drill.

He adopted the drill into his modern technique shooting method.

Since then, the drill has been taught at Gunsite Academy and expanded into numerous armed forces and police agency training programs.

The United States Marine Corps teaches the Mozambique Drill under the “Failure to Stop” namesake as part of their various Table 2, Table 3, and Table 4 rifle shooting courses of fire.

Marines conduct the Failure to Stop Drill at various ranges with a service rifle, and it utilizes various pivots and movements.

Why the Mozambique Stays Around

A big reason why the Failure to Stop Drill or Mozambique Drill stuck around so long is that it’s efficient.

The Mozambique focuses on practical shooting and, most importantly, shot placement. Chest and headshots are both showstoppers in violent situations.

Second, look at how the Marine Corps uses it.

They adapted it to a rifle, implemented night vision, various ranges, and movements to gain more out of the drill.

You can take the Mozambique Drill and tweak it to various training scenarios and situations.

Though the Mozambique started life as a handgun drill, it can be easily adapted to rifles or SMGs.

With a rifle or other long gun, you should increase the distance to create more of a challenge and take advantage of the rifle’s features. At the same time, focus on working on important skills and efficient shot placement.

It’s also a drill that’s easy to do but hard to master. The drill gets even harder when you implement various movements and ranges.

As time changed and situations evolved, we saw the rise of body armor.

It’s become more common, and the Mozambique is an excellent drill to work for countering body armor. Two shots to the chest will stun even the most heavily armed opponent.

That slight stun and stagger of two rounds to an armored target’s chest buy you the time necessary to place a properly aimed shot at the unarmored head.

While I doubt this was a major consideration when the drill was adopted, it has become a reality of modern gunfighting.

Mozambique Drill Variations

1. Two and a Knee

When armed with a rifle, you have a longer effective range overall. However, as the range increases, the ability to take a final headshot diminishes.

As such, one rifle variation challenges shooters to take two shots to the chest and then take a knee and take a final headshot from a kneeling position.

It’s a challenge, but learning to take a knee makes you a smaller target and allows you to adopt a better-supported position.

2. Move and Mozambique

A USMC variant of the drill challenges shooters to conduct a Mozambique Drill on the move. Shooters start at a longer distance than average.

With a rifle, start at the 25-yard line, and with a handgun, start at the 15-yard line.

While moving forward, fire two shots into the target’s chest, then stop moving and take a final well-aimed headshot.

I prefer to utilize this drill with an element of cover that I’m moving towards. I take the final shot from behind cover.

So, if I’m starting at 25-yards, I have the cover placed at 17-yards. I take the two shots to the chest while moving somewhat slowly.

After the two shots, I keep my weapon on target but move much faster to cover.

3. The Box Drill

The Mozambique Drill has also been adopted into the Box Drill — another favorite of the Marine Corps.

A Box Drill involves two targets but retains the core of the Mozambique.

Shooters start on either target, fire two shots into the chest on the first target, then transition to the second target and fire two shots.

On the second target, the shooter transitions upwards and takes a headshot. Finally, the shooter finishes the drill by transitioning to the first target and taking a final headshot.

This drill was famously used in the film Collateral, albeit the final headshot Vincent takes is somewhat optional.

Conclusion

The Mozambique Drill has been kicking around for the better part of 50 years now. It’s seen use in numerous police and military training courses around the world.

And rightly so – it’s efficient, easy, and adaptable.

Do you utilize the Mozambique Drill? Let us know below the why or why not. Want to save money on ammo while training? Check out our list of Low Round Count Drills.

5 Leave a Reply

A must master drill that will save your life!

Fascinating article! I knew some of the history behind this drill but not all, so I learned something. That's always nice. I led a women's gun group for seven years and of course we had a secret password. It was... "Two to the chest and one to the head." Thank you for explaining the two-target version. I'm going to practice that today.

I have only been in one fire fight more than 65 years ago (I am eighty-one years old now). At that point I had no fire arm training what so ever. Fortunately, I got lucky and emerged unscathed and victorious. I started carrying 4 or 5 years ago and I train as often as I can. Almost all sessions I start and end with the Mozambique Drill. I even do it with my dry fire practice. My plan is to live out my life without another gun fight. But, I believe I am ready if it should happen. Thanks for a great article.

Thank you for a good exercise idea and also the history behind it.

This is exactly what we learn in the defensive firearms classes I take. Vital organs in the chest cavity are the larger target and key to hit first, it will be easier and faster to hit than a head shot. The bad guy may or may not have armor, even if he doesn’t your initial 2 chest cavity shots may not have done as much damage as you would like or just poked holes in him with pistol rounds., with the bad guy slowed down you can have a couple extra seconds to place a head shot (aim for area around eyes, nose, sinus cavity not the Hollywood forehead shot in movies as the frontal bone that is part of our skull is super strong and thick and can deflect bullets)