Let’s face it; machine guns are a different kind of cool.

There’s something pretty rad about a gun that can spit out a bunch of bullets in the blink of an eye.

Even before I was a machine gunner in the Marines, I was fascinated by big, belt-fed weapons.

Like most kids of the 80s and 90s, guns wielded by Rambo, Jesse Ventura, and other action movies looked awesome.

But what’s the origin story behind these fascinating pieces of machinery? Glad you asked…

We’re going to explore the history behind machine guns and walk through the iterations over the years.

By the end, you’ll be able to spout some cool facts about these rapid-fire guns to your range buddies.

So, keep reading to learn more…

Table of Contents

Loading…

Early Attempts at Rapid Fire

During my Marine days, I was tasked with teaching various classes on machine guns, including the history of machine guns.

As I began researching this topic, I quickly discovered that we’ve sought ways to make guns fire faster since the early days of muskets.

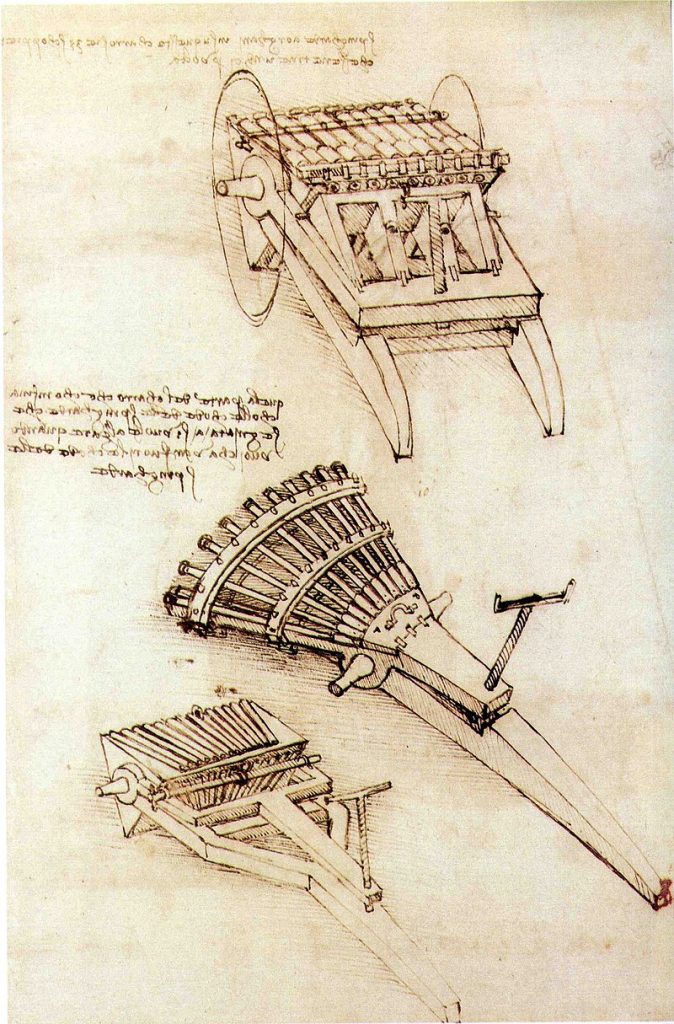

In the 14th and 15th centuries, the ribauldequin, also known as the organ gun, arrived.

An organ gun was a mass of barrels designed for volley fire.

These firearms could use a dozen different barrels and were used as anti-personnel weapons.

We saw early repeating muskets like the famed Puckle Gun enter the scene in 1718.

While the Puckle was not a machine gun by today’s standards, at the time, it was labeled as such.

In reality, the Puckle was a manually operated, crew-served flintlock revolver cannon.

This tripod-mounted, single-barrel weapon was never used in warfare, and very few were ever produced.

However, the idea persisted with dozens of “machine gun” muzzle-loading cannons invented along the way.

Numerous patents and designs came and went in different eras, but few ever caught on.

Until one of the most famous rapid-fire guns of them all…

Enter Mr. Gatling

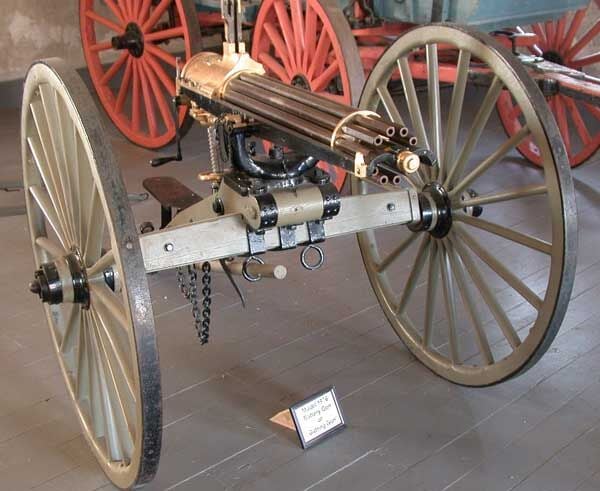

Richard Jordan Gatling designed the Gatling Gun in 1861.

While not technically a machine gun, the Gatling established what a sequential firing weapon could do.

Utilizing multiple rotating barrels and a hand crank design, the Gatling gun introduced a heavy, crew-served gun fed from a top-mounted hopper.

An assistant gunner could continuously load the top-loading hopper as the weapon fired. And much like a modern belt-fed weapon, it could be fired without reloading.

Because Gatling guns are crank-fired, they’re not technically (or legally) machine guns; therefore, you can own one without any NFA hoopla.

In the 1860s, the Gatling gun offered unparalleled firepower for the time and served the United States for decades.

Interestingly, the inventor of the Gatling gun invented the gun to actually reduce deaths on the battlefield.

After witnessing thousands of Americans die during the Civil War, he believed his weapon would prevent the need for large armies.

The logic? Smaller armies would mean fewer casualties.

As we know, he may have been wrong. But he wouldn’t be the last to think that a rapid-fire gun could reduce death and help end man’s lust for war.

The First Real Machine Gun

“These are the instruments that have revolutionized the methods of warfare, and because of their devastating effects, have made nations and rulers give greater thought to the outcome of war before entering…They are peace-producing and peace-retaining terrors,” The New York Times published in 1897.

These instruments the famed paper referred to…the Maxim machine gun. Reality would prove much different than the paper’s opinion, though.

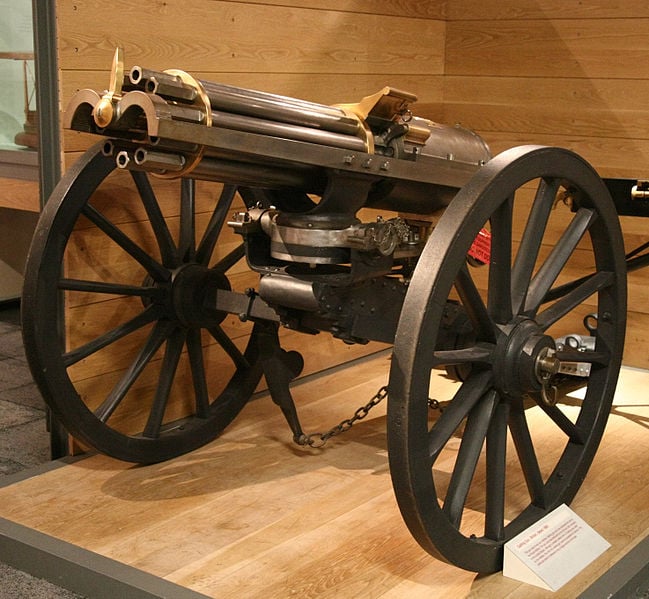

Hiram Maxim was a prolific inventor with dozens of inventions to his name, including the Maxim Gun.

An American inspired him by saying, “Hang your chemistry and electricity! If you want to make a pile of money, invent something that will enable these Europeans to cut each others’ throats with greater facility.”

Taking that advice, he set up shop around 1881 and spent the next three years working on the first real machine gun.

In 1884, Maxim had a working prototype of the first Maxim Gun.

Maxim’s weapon worked on the short recoil principle that uses the recoil of the previously fired round to operate the weapon’s fully automatic capabilities.

Short recoil often finds itself in handguns, but the Maxim Gun was the first to utilize this to create repeated fire.

A 250-round reloadable canvas belt fed the Maxim Gun, chambered in various rounds.

Typically, cartridges were full-powered rifle rounds like the 7x57mm Mauser cartridge and the .303 British.

With a 550- to 600-round per minute fire rate, the gun terrified everyone — from reporters to seasoned officers.

To keep the barrel from melting, the weapon featured a water jacket. Though this prevents melting, it adds extra weight and increased logistics.

Weighing 60-pounds, it was mounted on a wheeled base for transport.

While large, the gun proved more portable and maneuverable than other mechanical guns like the Gatling and Gardner guns. It could rotate on a cam and change direction easily.

The Maxim Gun didn’t become an instant success. However, a forward-thinking Commander in Chief of the British Army convinced the British to purchase 120 Maxim Guns chambered in .577/450 caliber.

As you’d imagine, a black powder machine gun made quite the cloud of smoke.

Before the Great War

Though World War I often receives credit for the advent of machine gun dominance, several events before WWI served as a precursor to the machine gun’s dominance.

A Maxim machine gun was sent with the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition in 1886 — one of the final large European expeditions in the heart of Africa.

Reportedly the Maxim Guns terrifying noise and chatter often scared attackers, allowing the colonial expedition to successfully retreat from central Africa.

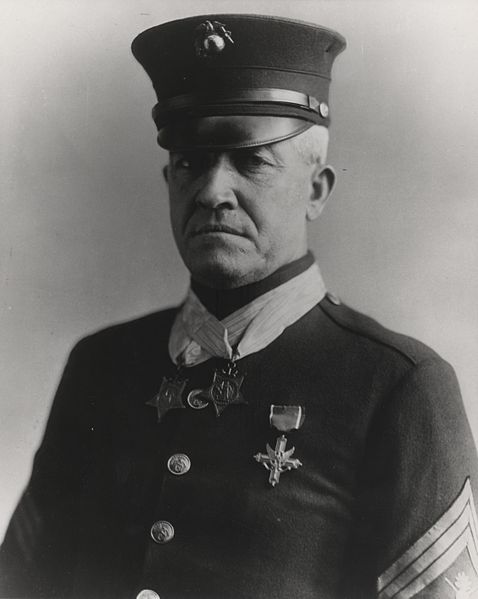

The United States involved itself in several small conflicts worldwide in the early 1900s — involving Marine Dan Daly, machine guns, and Medal of Honors.

In 1900, Daly wielded a Colt-Browning 1895 “Potato Digger” machine gun to hold off Chinese Boxers attempting to seize the fortification he was protecting.

One man held off wave after wave of attackers, reportedly killing over two hundred boxers and earning his first Medal of Honor.

Fast forward to 1915, Daly found himself in Haiti, leading a 35-man platoon.

After the platoon came under heavy fire, they lost one of their machine gun in a river they crossed.

As night set in, they held firm. But without the machine gun, they were incredibly vulnerable against the 400 attackers surrounding them.

Daly slunk into the darkness, slipping into the black surface of the river. By some miracle, he recovered the machine gun and got back to his men.

The next morning, they struck out and destroyed the surrounding force with supporting fire from the machine gun.

Daly received his second MOH and would later receive more decorations during World War I.

Small conflicts like this all involved the machine gun at some small level.

Machine guns were created en masse, and new designs began improving upon the old.

Right around the corner, though, crept the war that would change everything.

World War I

World War I is the machine gun war…or it’s the war that allowed machine guns to change warfare.

Every side during World War I utilized some form of the Maxim Gun, as well as other machine guns often domestically produced for fighting forces.

World War I created such a need for machine guns that nearly a dozen variants were produced.

To illustrate how many machine guns were used in World War I, look at the U.S. Army Machine Gun doctrine.

Americans issued four machine guns per regiment in 1912. But by 1919, a regiment wielded 336 machine guns.

The Brits refined the Maxim Gun into the Vickers Gun.

Vickers purchased the Maxim company, modernizing the Maxim for the time.

The Vickers featured increased reliability, nearly a 20-pound reduction in weight, and produced models for use in aircraft.

We saw guns like the Hotchkiss M1914 and Browning M1917 enter the fray as modern heavy machine guns.

The old Colt Potato Digger even saw service in the Great War.

The advent of light machine guns also made automatic weapons easier to maneuver and carry.

Though these guns do not fit the modern definition of a light machine gun, they served as examples of the time.

Early light machine guns like the Lewis Gun, the Chauchat, and the BAR brought magazine-fed machine guns to the front lines.

They offered a portable source of fire that didn’t require mules to move.

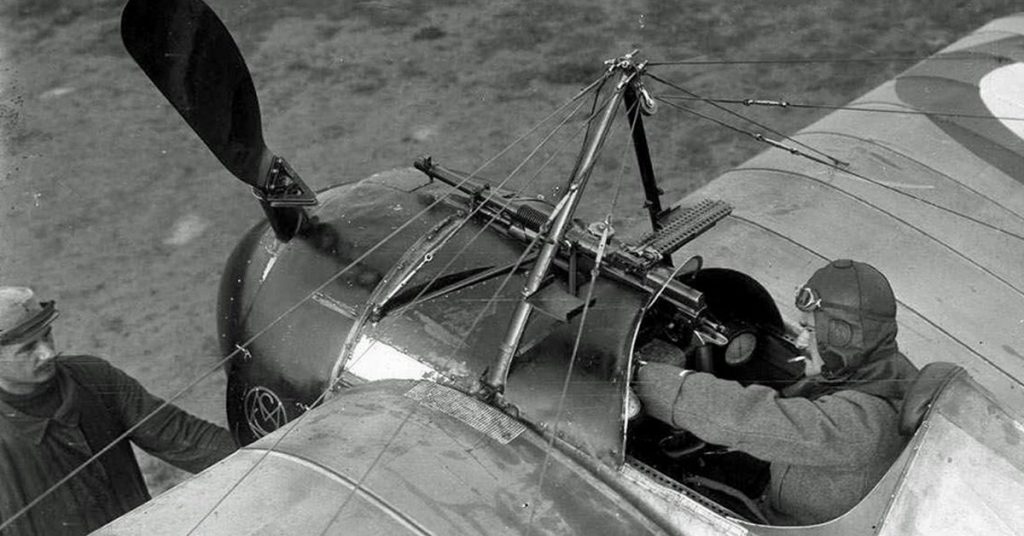

World War I also saw machine guns take to the skies mounted in early fighting planes.

At first, the design proved problematic. Guns mounted behind the propellers would quickly destroy the propeller.

Eventually, the Imperial German Flying Corps found a way to synchronize the gun to the propeller, better timing the gun’s firing to avoid destroying the propeller.

After a bit, the Allies figured it out as well, and machine guns took to the skies for everyone.

Before machine guns, the human wave attack ruled. Slow-firing weapons allowed forces to charge.

But machine guns changed that.

These firearms killed thousands of men attempting the human wave attacks. Soon, machine guns sent men to the trenches, creating a new form of warfare.

Enfilade fire meant a burst of machine-gun fire could kill several men grouped together.

Advances became loose and dispersed to limit a machine gun’s effectiveness. The traditional cavalry was killed in both literal and doctrinal ways.

British Field Marshal Sir John French once said, “The machine gun has no stopping power against the horse.”

Though, horses still served a purpose as beasts of burden dragging carts, makeshift ambulances, or ironically as means to move heavy machine guns.

After the creation and fielding of the machine gun, warfare would never be the same.

To read more on guns of WWI, check out our piece on the Famous Guns of WWI.)

World War II

In the years leading up to World War II and during, we saw machine gun technology improve.

Guns got lighter with designs like the M1919 from Browning. They also got bigger with 50 caliber machine guns like the M2 “Ma Deuce” machine gun.

Light machine guns also lessened the weight and became less complicated with improvements to the BAR and the introduction of the Bren light machine gun.

Russians utilized the pan magazine-fed DP-27, the DS-39 medium machine gun, and their own .50 caliber DShK.

Germans were huge believers in the machine gun in World War I and remained stout followers after the Somme.

They created the best machine guns of World War II in the form of the MG 34 and later the simplified MG 42.

These guns combined the belt-fed designs of heavy machine guns with a relatively light weight of 26ish-pounds, depending on the model.

German engineers added stocks and bipods to make the weapon man-portable. And they featured a fearsome fire rate that earned them the name “Hitler’s buzzsaw.”

The MG 34 and 42 were the first general-purpose machine guns.

GPMGs are designed to work with the infantry, on tanks, trucks, APCs, on the defense and offense…basically, the Swiss Army knife of machine guns.

Lessons learned in World War I brought forth two new infantry tactics — both built around the machine gun.

Americans championed maneuver warfare, relying on machine guns to suppress the enemy so riflemen could destroy Nazis.

The Nazis utilized tactics built around the machine gun as well. Riflemen funneled the enemy in front of the machine gun and allowed it to do the damage.

Once the world’s most fearsome evils were dealt with, machine advancement was rather slow.

Throughout Korea and other small conflicts, World War I and World War II weapons were the standard.

However, behind the scenes, work commenced to shrink machine guns and lighten them.

The Allies took note of the MG 34 and MG 42 and began creating their own GPMGs.

Read more about guns from WWII (that you can still buy) here!

The Not So Cold War

During the so-called Cold War, the GPMG ruled. Everyone wanted a versatile, man-portable gun that could occupy a wide variety of roles.

Three guns largely define this era…

The American M60 appeared in 1957, replacing the old M1919 and BAR.

Meanwhile, the Russians came out with the PKM, a 7.62x54R machine gun that served as the Warsaw pact GPMG. It also found its way to Asia and the Middle East in large numbers.

Finally, the Belgian design FN MAG became Western Europe’s GPMG of choice.

At the time, the Russians led the way with the first modern light machine gun — the RPD.

The Ruchnoy Pulemyot Degtyaryova combined a man-portable machine gun chambered in an intermediate cartridge that was belt-fed and designed to function at the squad level.

It fit between the PKM and the AK series of rifles, offering a lightweight, high-volume tool for maneuvering elements.

But the American war in Vietnam showcased the lack of capabilities of the M60. It simply wasn’t as robust or reliable as other options.

U.S. machine gunners got plenty of firepower behind the gun, but the M60 was quite heavy and usually assigned to a dedicated machine gunner.

American soldiers needed a belt-fed light machine gun.

Eugene Stoner worked on the Stoner 63 weapon system, which had a light machine gun component.

That light machine gun found favor with the Navy SEALs. But it was thought to be too complicated for the Average Joe as it was finicky and needed heavy levels of cleaning and oiling.

Vietnam also brought us the unbeatably cool Minigun.

The Minigun gains its name from the 20mm Vulcan gun it’s derived from. Originally called the Mini Vulcan, it eventually just became known as the Minigun.

The Minigun typically rides on top of vehicles and is even popular on helicopters. It can deliver up to 6,000 rounds per minute.

This massive 7.62 gun opts for six barrels, powered by an electric motor to deliver an unparalleled amount of fire.

The Modern Era of Machine Guns

American forces weren’t the only ones in search of a light machine gun. The Belgians also wanted in on the action.

So, in 1974, FN created the 5.56 chambered FN Minimi – bridging the gap between the assault rifle and GPMG.

But that wasn’t the end of light machine guns. They came from various parts of the world.

The Minimi and RPD (and later RPK) were the most popular in service. Around the world, we also saw designs from Israel, South Africa, and China.

Western military forces adopted the Minimi, followed by several Eastern European forces modernizing their military in a post-Soviet world.

Americans eventually adopted the Minimi under the moniker the M249 SAW.

The Minimi gave militaries a belt-fed light machine gun suitable for squad support.

Users had access to a quick-change barrel system – giving the Minimi an edge over the RPD.

Beyond that, America joined the rest of the world by adopting the FN MAG or the M240 to replace the less reliable M60.

While the M240 was heavier, it is painfully reliable in adverse conditions.

Vietnam also saw the invention of what’s arguably the coolest machine gun…well, machine gun might be the wrong name.

It’s a machine grenade launcher.

A belt-fed, full auto grenade launcher sending out 360 grenades per minute.

It’s an absolutely awesome system that is so utterly fun to shoot!

The Mk19 proves scary effective and destroys whatever gets in its way.

The Future of Machine Guns

Though machine guns have come a long way, they still retain one problem plaguing them from the very beginning…they’re heavy.

Even light machine guns feel heavy compared to rifles. This alone has driven the Marine Corps to ditch the SAWs in favor of an Infantry Automatic Rifle.

The automatic rifle has also seen use with a few different military forces, including the Brits. In comparison, the Russians have long used the RPK series of machine rifles.

GPMG’s struggle to lose weight more than me when Christmas comes around. But the M240L trimmed some, and the Army seems to like it.

Recently the Belgian machine masters at FN released the Evolys machine guns in 5.56 and 7.62 NATO.

Both weigh less than the M249 SAW and use advanced recoil reduction systems to maintain controllability.

(Read more on the Evolys from a machine gunner’s perspective here!)

On the flip side, Special Operations is seeking a smaller heavy machine gun or one that can bridge the gap between the .50 BMG M2 and 7.62 NATO guns.

Sig’s MG338 seems the likely leader in this role.

The MG338 fires incredibly powerful and potent .338 Norma Mag rounds.

This grants users an effective range of 2,000 yards with a massive increase in energy and penetration over the 7.62 NATO rounds.

Heck, the MG338 is even a little lighter than the M240.

The future seems lighter and more capable, with guns better suited for non-traditional warfare.

Beyond that, we might see the rise of an extra-medium machine gun with more power and range than a traditional GPMG.

Conclusion

Machine guns are fascinating firearms. Often ignored since the NFA and Hughes Amendment make it impossible to own a modern variant.

Despite that, they come with a fascinating history that changed the face of warfare completely.

If I’ve missed anything, or you have a notable gun that deserves mentioning, drop it in the comments below! If you dig history and love more full autos, check out our dive into the HK MP5. It’s a classic!

1 Leave a Reply

One correction, the Hiram Maxim who invented the Maxim machine gun is the FATHER of the Hiram Maxim who invented the silencer. I've heard it described that Maxim Jr. hoped to prevent in other firearms enthusiasts the deafness his father developed after years of firearm experimentation.